That’s Luscious - No, Excuse the Freudian Slip: That’s Lucian! The Etchings of Lucian Freud at MGB

- Christian Hain

- Aug 12, 2017

- 6 min read

Updated: Mar 25, 2020

(Berlin.) This summer, Martin Gropius Bau opens its doors to a Swiss bank. Speaking simply of a promo event would not be fair, though: UBS has amassed an eminent art collection with some thirty-thousand assets to spice up their portfolio and PR strategy. Employees are treated to frequently changing displays in conference rooms, executive offices, and possibly even the restrooms. Certainly trumps the Ficus tree your boss has offered you.

And still, that bonus probably imports more to high potentials (you don’t say “hipos”, do you?) seeking a career “in finance”. Most often, it's enough to buy a lot of art or two, at auction.

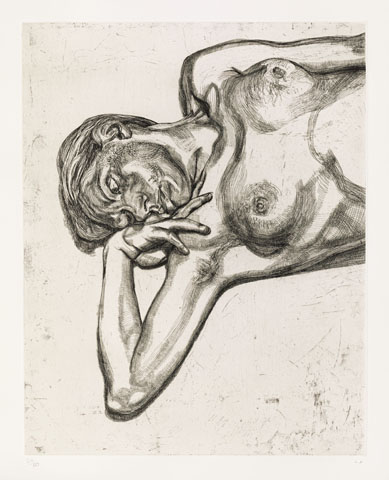

Occasionally, art gets involved in a bigger deal: In the course of a takeover seventeen years ago, UBS secured fifty-two works of Lucian Freud (the then CEO of Paine Webber rather not forgot them when clearing out his desk). The small etchings – the plates at the origin of these final papers - the artist executed “live”, in the presence of his model, putting the plate on an easel. The collection was most recently shown in public at Denmark’s Louisiana Museum in 2015, it may now be admired in the first Berlin exhibition of Lucian Freud since 1991. Sigmund’s grandson was a native Berliner, but forced to flee and settle in London in 1933, where – I only mention this for the art ignorant who miraculously stumbled across this webzine – he died in 2011 being widely acknowledged as one of 20th Century greatest painters.

Listening to an expert, you occasionally do learn something new, for example that Lucian Freud had a Francis Bacon nude hanging at the foot of his bed. Their friendship, however, turned sour after some nasty art criticism from Bacon’s part.

Lucian Freud, who most of the time recruited his models among personal acquaintances – the odd exception apart, like a portrait of her Royal highness Lizzy W. which he painted at her place, and he thoroughly enjoyed doing it, as tells again the expert, Mr Richard Cork, who contributed to the catalogue and attended the Berlin opening – Lucian Freud, I say, told sitters to make themselves comfortable. But unless you’re a seasoned Yogi, the most comfortable pose will inevitably turn to torture when you’re forced to keep it for hours. The tension, the cramped, spastic, victimized, position transmits itself to the image, and becomes crucial to the impression of suspended motion that prevails in large parts of Freud’s œuvre. The painter’s “victims” cannot stand it any longer, they long to get away, to move, breathe freely, and the image captures and emanates the sensation. Freud imbued the paper with vitality through suffering. Man is not made to be static. Struggling as turned to stone or sculpture, but whoever said, immortality was attainable without pain? Comfort and happiness are but fleeing phenomena. Via its very absence, Lucian Freud implies the import of motion, of time and art’s (desperate? futile? heroic? all-important?) resistance. But easy here. The visit to MGB starts with a photo portrait of the man himself, and a fox: David Dawson, Lucius with Fox Cub, 2005 (so that’s where Jürgen Teller got the idea from!). That same David Dawson, one of the master’s s̶t̶u̶d̶i̶o̶ ̶s̶l̶a̶v̶e̶s̶ assistants, appears in an etching, with buckteeth. The initial impulse to search your pockets for a carrot soon gives way to admiration for the artist’s ruthless honesty. Not as an aims in itself, not to mock the model, but to celebrate his uniqueness.

The approach extends to closest friends and family: The artist’s daughter Bella is not “bellissima”, her face severe, masculine but doughy, too wrinkled for her age. Her father did not spare her. Googling for her today, she little resembles the picture (any more), but this is how he saw, and how he wanted to show, person and personality. Many mention the autobiographical aspect of Freud’s work, his knowledge of his sitters was not limited to the outer shell. Like every painter, he sought to show what “really” is – real to him. He trusted his interpretations, his vision. If he focused on weaknesses, he did it for truth, for their belonging to facts he perceived to portray. To the eyes of the beholder, beauty does not exist. If Freud only sought to copy an image, he could have become a photographer, if uncaring for aesthetics an installation artist. But to him imported most his vision of an image's "content", its relevance, its meaning. In a way, Freud is tremendously classic. Creating artificial nature, that’s art!

Lucian Freud is quoted with comparing paint to flesh, and maybe this explains his prevalence for those who are endowed with more meat than others. Rubens shared similar ideas. The canvas is filled more quickly, with less need for a background. On the other hand, he also did a portrait of Kate Moss once (not in this show). Lay bare the truth, show their weaknesses, or not even that, because it would be a judgement, but depict what is, unfiltered, the story, the now as given. That’s also a characteristics of photography. But more “real”, somewhat more true, and more alive. The mystery what is pose, momentary, and what character, must remain unsolved.

At least in titling his works, Lucian proved a friend to his friends. The Head of a Naked Girl (2000) not really belongs to a girl, she has not been one for years. The same woman he painted in oil a year earlier, one of three paintings at MGB adding to the collection of etchings (but also owned by the bank). Contemplating it, you wonder - is it a female at all?! Let’s assume, this specimen self-identifies as the image of a human being. A Reclining Figure focuses the bald top of a head - talking of a reclining hairline would be euphemistic, this is about final decline. And a Man Resting might also be embraced by sleep’s brother, is this rigor mortis? Life and death mingle in the absence of time.

There is Cerith (fellow artist Wyn Evans), 1989, one of a handful identifiable sitters, bloated, plump, puffy. Another is the artist’s lawyer, Lord Goodman, who appears in pee-yellow pyjamas. Those unnamed might feel grateful, a Head of an Irishman calls to mind Boris Karloff in character. But all of them, and maybe most of all the bearers of a Head of a Woman, of a Girl 1 and 2, have lived. It shows. Frequent are the comparisons to Freud’s famous granddad, but in how far do Lucian’s drawings reveal the character, the personality, more than simple pose, a mood, a moment? Frequently we are tempted to infer a character from a face, to profile the model, to interpret a personality expressed by visual traits, but that’s a slippery slope. Take A Man Posing who also is a man exposing. The image seemingly grants a glimpse into the nude’s exhibitionist psyche. Or does it? He’s certainly “made himself comfortable” - and us rather uncomfortable -, but he’s posing for an occasion, acting. Alive, not living.

The milieu is missing, no context there to guide us, and he would be a bad psychologist who issues his verdict without talking to the person subjected to his theories and ideas. We don’t know a thing about this Woman With an Arm Tattoo, except that she’s a woman with a tattoo on her biceps and “eating” presumably counts among her favourite pastimes. It might be Sue from Large Sue (Benefits Supervisor Sleeping) (a rare example of context in the title), or it might not. Is she dreamy, sad, or praying for the session to end soon? The image cannot surpass the situation, her mind remains impenetrable. “I would wish my portraits to be of the people, not resemble them. Not having a look of the sitter, but being them”, Lucian Freud said. It is impossible.

Maybe, the true link between Lucian Freud and his grandfather is a subtle refutation, or – put kindly – an acknowledgement of the limits of an art. The human frame, the person, fascinated both, one wanted to cut it up in categorized types, confusing statistics with causality, or no, that’s what his disciples made from his ideas, the other was concerned about the individual truth of what is given. Where Sigmund tried to reach behind the outer shell, Lucian proved how hard it is to only describe, let alone explain it.

Freud’s portraits of flowers are less impressive, he should have left that to others. His portraits of pets, mostly dogs, on the contrary reveal a difference. They are relaxed. They don’t pose, they are what we have lost in evolution: pure moment. They are now, and fully belong here. Pluto, the family’s whippet, appears in numerous works (whoever wrote the wall texts for the show: ‘Pluto’s protruded claws signify tension’? That’s surprising. Did I miss something, e.g. Pluto being a cat in disguise?), once with a human companion for staffage. The woman must hurt, she’s tense, and thinking, while Pluto does not pretend – or care (and yet is ever alert). His pose is natural, or none, to him, and him alone. In the absence of authoritative norms, of culture, roles, whole worlds, created by their own minds as an endemic power, non human animals appear more equal, more one alike the other. It’s a vision for mankind, a lot of people share today. Be one, don’t think beyond the moment, be happy and consume, don’t trust any label that exceeds, and thus poses a threat, to what is "natural". But this probably does not belong here.

Lucian Freud, Closer, 22 July-22 October 2017, Martin Gropius Bau

World of Arts Magazine – Contemporary Art Criticism

Comments