Protest This - Martin Luther and Other Protestantisms in a Historic Show, at Martin-Gropius-Bau

- Christian Hain

- May 3, 2017

- 7 min read

Updated: Mar 25, 2020

(Berlin.) The German government puts much effort into celebrating Martin Luther this year. Nailing his 99 problems - no: 95 theses - on a church door in the small town of Eisenach five hundred years ago, the rebellious monk unwittingly started a movement we know as “reformation”, or “Protestantism”, today. Luther was only the first in a long line of reformers, it needs to be noted, and who knows if Zwingli, Calvin, ea. would not have done as they did even without him. The federal festivities commenced with an exhibition in Dresden two years ago already. Now, in 2017, there will be three more in Berlin and the reformer’s places of residence Wittenberge (a ninety-minutes-drive from the capital) and Eisenach (about double that distance). The government trusting a PR agency with the details, they all appear under a common title: “The Hammer” (website: www.3XHammer.de, yes, that’s “Triple-X-Hammer”, but don’t be afraid, it’s not some obscure German ‘special interest’ site, really not). MC̶L Hammer. But why?

Malleus Maleficarum, the infamous Witch Hammer was published only three years after Luther’s birth in 1483, a bestselling symbol of fanatic Catholicism and the ugly face of inquisition (though never officially endorsed by the church)? Or is it about ‘hammering the papists’? No, this would all be overestimating PR minds - “Nice, dude: ‘hammer’, so catchy, force of change and stuff, y’know?!” seems much more like it. And it could be worse still, like “He nailed it” (or: “He nailed the Pope”). I would actually be disappointed if this did not pop up in brainstorming.

To be fair, they justify the "Hammer" as a reference to the (rather mythical) posting of the theses. Interesting: In German, the term is Thesen-Anschlag, and ‘anschlag’ (“posting”) can also mean ‘assault’, or ‘terrorist attack’. – The attack on that Christmas market at a Berlin protestant church last December was strictly spoken the same. Only the theses seem more radical, or less fitting the local/temporal context. Maybe this is the true relevance of “Reformation” today: A radical Mohammedan feels not much different about modern civilisation than those early Christian reformers did about theirs. Let’s not compare the bloodshed they have caused so far; the medieval Christian schism with its 30 Years (Civil) War (1618-1648) devastated “Germany” more than even WW2 would do all these centuries later.

The Luther Effect. Protestantism – 500 Years in the World, hosted by Martin-Gropius-Bau and a historic museum, opened shortly before Easter. Some theologians might have preferred Pentecost, but perhaps they understand Protestantism as an execution and resurrection of the “true” church. Co-sponsored by the Federal Association of Savings Banks, that website also has a B2B section. Nobody cringe: They proudly insist on the influence, Protestant Christianity exerted on social market economy (a particularly German term for money with morals; don’t worry, it’s still money first). Reformation furthermore started the “European expansion” as a historian on MGB’s opening press conference put it, a cute euphemism for colonialism. That had started only shortly before, to thrive under the new spirit. Following the Renaissance of antiquity, reformations of all sorts suddenly were fashionable; something, anything, new was to be the next big thing while the ruling powers indulged in luxurious tyranny. We learn, this was a worldwide phenomenon, and still, citing the 1539 death of Guru Nanak, founder of the Sikh religion, in this context, seems odd. When talking about global synchronies, coincidence is in general more probable than teleology. Some religions by the way are still waiting for their reformers.

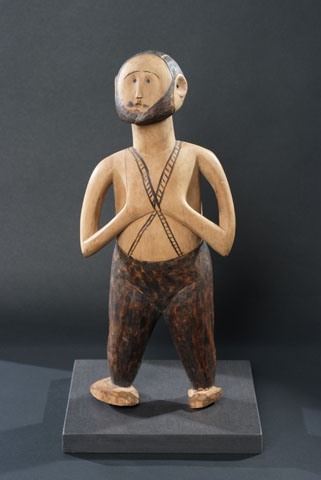

The Luther Effect talks not much of Luther, you are supposed to know his story already. Instead, the curators seek to provide an overview on the history and state of Protestantism in the world, “in the world” for practical reasons being limited to examples from the US, South Korea, Tanzania, and Sweden. If you’ve visited here before - and travelling to Berlin, the MGB is a must -, you might notice that they've never had a comparable budget before. This is a huge show, with video screens everywhere. Together with photo panels that are likewise suspended from the ceiling, they introduce individual protestants in quotes and short biographies. The examples range from theologists to students to preachers (including a particularly unpleasant example of a Televangelican, or at least his feisty face looks like it; I admit, I didn’t stop to listen), and a 19th Century American slave. All this mixes with historic exhibits: documents, artworks and artefacts, books and paintings.

MGB cites a bon mot: “When three Germans meet, they form a club, but two Americans suffice for a church.” The exhibition’s US chapter has a copy of the Declaration of Independence in contemporary translation, and otherwise focuses on “religion and slavery”. Documents tell of the competing views from abolitionists, slavers, and early “black churches”. They don’t discuss why modern era slavery was more of a protestant affair than catholic (with the exception of France).

Protestantism generally stands for rationalism, for less pomp and ceremony (and art) than other, older, currents of Christianity. This, of course, does not exclude fanaticism, fighting “heresies” was no less a burning desire for the reformers. The US, a country established by religious sects, by people who found themselves persecuted in the old world either for being free-spirits, or deluded extremists, started off as a haven for Protestants of all sorts. However, the Quaker project of a perfectly tolerant community soon faltered and gave way to new forms of fanaticism. But Salem is absent here.

To the eyes of many, “Missionary” is an abject profession, with a job description something like this: Seek to destroy other cultures, murder - literally of spiritually - everyone and everything that is different in the world, reduce diversity. But they actually do some good, too. Various examples show the Protestant conquests in Asia and Africa. In Tanzania, their share rose from 11% to 29% between 1970 and 2010, while “so-called local religions” declined from 31.8 to 1.8%. This seems slightly less shocking when you read the rest of the map: the population in the same period jumped from thirteen millions to forty-four millions. A German photo journalist documents the spiritual life in Tanzania, including an exorcism (yep, that’s not catholics only, either). Still, you cannot help thinking, this is not their tradition, not their form of worship, not their culture. But maybe it promises more success in the world.

For the Korean part, a cycle of drawings imagines, If Jesus was Korean. Nothing changes but the phenotypes and clothes of those featuring in the stories. Some South Korean Christians seek to reconcile with the North and Northern Korean Christians (excuse me, but: Who?! Fatty Kim is not exactly known to favour other cults than his own), others don’t. The country’s division was a main reason to include it here - not because Reformation historically means division, and it's proud about it, but because Berlin.

An installation by Hans Peter Kuhn in the main hall is the only work of contemporary art here. The artist explains it as a metaphor for both, Catholicism and Protestantism. The one is described by a roof, or a “horizontal wall” that, like the Catholic priest and the church, is blocking the immediate access to heaven, and the other by vertical walls. Where a catholic may sin at will - as long as he confesses and repents after the act -, the protestant is supposed to live in perfect boredom. Looking at the installation, you won’t easily recognize those explanations. It more resembles wings in a wave movement, or even a double helix. The "walls" are lines of steel rods, and thus transparent. It’s tough, though: Had he used “real” walls, it would be just a house. I’m taking bets, the artist who is known for working with sound - the installation is accompanied with recordings from church events all over the world - took inspiration from that quite baffling revelation of being “happy like a room without a roof”, as heard on the radio.

Visitors only walk on the sides, and never reach the centre, they are constantly led around the focal point. Take care not to trip on the glass floor, or the rubber mats, and go immediately to heaven, or worse.

A celebratory anniversary exhibition like this obviously won’t discuss more complex questions, or try to explain where Protestantism’s historic success resulted from. It is true that, on the one hand, Protestantism was more “serious”, more about inward spirituality, as opposed to then Catholic worldliness. Yet, on the other hand, the “new” religion quickly proved more convenient to business, more useful and adapted to the world as well. There’s your capitalism-Protestantism thesis.

Maybe it was a mistake to offer reason and judgement to the people, while still sticking to the stories you've used before. The new belief stood at the beginning of the abolishment of religion in Europe. Protestantism first put man over God, suddenly people could choose between many “right” ways. One might observe: If you are allowed to choose between options that restrict your basic impulses, chances are you will eventually quit them altogether (those options). When people are trusted with every decision, they will eventually realize how random every rule is, all values, all customs, every culture. The own beliefs and rites diminish, they lose importance and relevance.

Today, science is even more useful to capitalism, itself the only force capable of uniting people(s) (in a meaningless nothing), while crushing every hindrance. Even in the US, “God’s own country”, traditions erode, and fanaticism is just a desperate, a temporary, way out.

Imagine a dinner with your Chinese colleague burping to signal approval, your African pal using only his right hand, &c. Soon, you'll stop paying any attention at all to how you use your fork (America stands example for the world once again). It doesn't matter, everybody may do as he pleases. And it’s a business dinner, you’re all happy because you sell, equality. No big thing, certainly not, only something is lost, a world that was created, a form of creation that was endemic to our species. It was called culture.

Sorry for the conservative rant, I’m taking no sides. Just playing God's advocate for a moment.

On the background of this event and the Luther festival, that alchemy show at Kulturforum suddenly appears in a different light.

The Luther Effect. Protestantism – 500 Years in the World, 12 April-05 November 2017, Martin Gropius Bau

World of Arts Magazine - Contemporary Art Criticism

Comments