For the Gold Digger in Your Life: It’s All About the Chemistry. Al-chemy at Kulturforum

- Christian Hain

- Apr 11, 2017

- 7 min read

Updated: Mar 25, 2020

(Berlin.) Much company they draw, and much abuse, //

In casting figures, telling fortunes, news, //

Selling of flies, flat bawdry, with the stone: //

Till it, and they, and all in fume are gone. //

When Ben Jonson introduced his play The Alchemist, first performed in 1610, with these verses, the discipline’s reputation for being less a science than a refuge for con- and madmen had long been established.

But there are multiple facets to everything, and alchemy can claim achievements that are still recognized today. Allow me to further cite the preface to a present edition of that play: “In the early 17th century, chemistry, which was usually known as alchemy (‘al’ means ‘the’ in Arabic), was dedicated to the production of pharmaceutical medicines and the scientific study of elements and their compounds. These twin purposes are reflected in the ambiguity in modern British English of the word ‘chemist’, which can denote both a pharmacist and a specialist in chemistry. The ultimate aim of pharmaceutical chemistry was the production of a panacea that would cure all diseases and prolong life indefinitely. The scientific study of chemicals was often skewed towards the aim of transmuting base metals into silver and gold. The subsequent development of chemistry has demonstrated that both aims were futile, but it cannot be safely assumed that alchemy was a pseudo-science (...).” (Gordon Campbell, in Ben Jonson: The Alchemist and Other Plays, OUP 1995/2008.)

The Dionysian side of science, the alternative, or meta-, knowledge, inherent to myth/religion/literature, has never been fully chased from human life yet. From Swedenborg and Mesmer to Huysmans and the hobby alchemist Strindberg, from the Golden Dawn writers’ craze to Aleister Crowley and every self-respecting songwriter of the 1960s and 70s, “irrational truths” regularly resurfaced on all levels of cultural production while society favoured icy rationalism. We’ve seen a lot of “spiritual” artist manifestos, and, it needs to be said, there has been the fascist side of esotericism, too.

It's always followed by a relapse into (this-)worldly logics. One explains life, the other makes it worth living – man’s craving for sense will never be satisfied with a mere inventory. Currently, we might stand witness to the birth of another wave, as the pendulum swings back once again. (This has few to do with politics, even though it seems hard to imagine, there once was a non-materialist, anti-enlightenment, Left.)

Alchemy could be described as the first ever theory claiming, “’tis not about interpreting the world, ‘tis about changing it”, and there’s even an artistic side that an exhibition at Kulturforum now seeks to explore. Alchemy – The Great Art has been co-organized with LA’s Getty Research Institute, where it – in a different version, many works are mutually exclusive to both events – was staged last winter. The curators Jörg Völlnagel and David Brafman are experts in the field, telling us how they spent many years on discussing, planning, and revising the project. Sometimes, this can become a problem. If you are too much interested in a thing, you tend to judge everything by its (twi)light. The show includes “alchemy” from all over the world and several millennia; there is European alchemy, Chinese/Taoist and Hindu alchemy. But what is alchemy, what magic, what is belief - and what basic, early, science? The limits, of course, are blurry, and there are no solid criteria to establish over-interpretation. For example, the production of pigment colours is celebrated as one of alchemy’s successes – or would you not rather say, of early chemistry? If Mayan priests correctly calculated planetary motions, is that an achievement of Mayan religion, or of scientific astronomy pursued by Mayan priests? The answer might not be as easy as you think (in what kind of exhibition would you include it? To what extent can science and ideology be separated at all?). Back to topic, Greek alchemists in colonized Egypt created Egypt Blue, the first ever "artificial" colour, and the spagyric – i.e. pharmaceutical - branch of alchemy evolved into today’s homeopathy. But was Hildegard of Bingen an alchemist, or a godmother of modern medicine; and which medieval doctor was not also a witchdoctor, invoking spells like any other remedy (most of them did)?

To justify this show at an art venue, the curators insist on a supposed kinship between alchemy and the arts, in that both are concerned with god-mimicking creation, and the transmutation of matter. – Yet, alchemy had a purpose: health or gold, or both, one might object; and that’s not, or ought not to be (openly), the case in art.

The story starts with a sculpture of the Olympian messenger service Hermes, a.k.a. Mercury, alchemy’s patron saint. He may not necessarily be identified with Hermes Trismegistos, the (likely mythical) founder of Hermeticism and proto-alchemist. Also important: hermaphrodites. (These are again highly in fashion today, self-identifying as alternative biological facts.) The lovechild of Hermes and Aphrodite who, after a friendly merger with the nymph Salmacis, got gifted with both skill sets, embodies the principle of unity that also lies at the core of alchemy. When everything is one, anything can influence everything else, everything can be turned, or split down, into something else. Hermes’ staff Caduceus - here lying to the feet of that sculpture - with two snakes is easily confounded with the Rod of Asclepius that sports one beast, whereas only the latter is (directly) connected to medicine. Oneness might also appear under the name of Abraxas (isn’t it great, how with a few catchwords you will appear an expert in the occult?), which might be symbolized as an Ouroboros, a snake eating its tail that in other words also signifies the eternal return, or samsara. Oneness further has a history in official theology; St. Augustine frequently cites Plotinus in this respect, and -

Stop.

This is highly confusing, and opens the way to endless plays of possible connections. A major problem of this show – and believe me, I think it is a great oone, one that you definitely ought to visit if in Berlin! – is how much information you have to bring along, and how much more you’re supposed to digest on the average visit of an hour and a half maybe. In the presence of other visitors (not to speak of the horrors of guided groups), blocking the view. The wall texts provide patrons with a basic understanding of the exhibits, but the question remains, whether the exhibition context is ultimately adequate.

You’ll see a lot of books, beautiful historic books. But to bow down and read a double page through the glass of a vitrine seems much less appealing than to sit down with a reprint, at home or in a library (and preferably a translated version, in a modern, readable, police). Better just treat it as visual art. That’s perfectly fine for that Mute Book in posters, or the metres-long Ripley Scroll (not her, but a monk and alchemist who for unknown reasons is associated with a magnificent illustration of alchemist beliefs and technics that first surfaced several decades after his death in 1490).

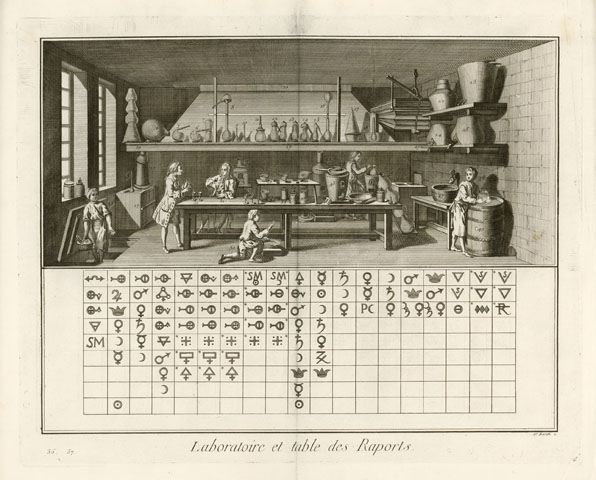

There are Chinese and Indian temple statues, and there’s jewellery and pottery that might or might not qualify as art. Most exhibits were once intended as didactic instruments, to convey information, or to teach other initiates. Some have never been fully deciphered. There is lab equipment, and drawings, and paintings from Rembrandt to Dürer, and Spitzweg. There is, of course, the story of German alchemist Georg Faust (unrelated to Manichean preacher Faustus) whose life inspired Faustian dramas from Goethe to Marlowe and Shelley's Frankenstein - the homunculus is just another produce of alchemist imagination (and its Kabbalistic side via the Golem tradition). A Swampman and Angel drawing of Jörg Breu the Elder (1582) might belong in this context; the creature in red, white and black colours is an embodiment of alchemy itself. It might have been an inspiration to Donald Davidson’s Swampman thought experiment about identity, completely unrelated to alchemy (I am indebted to a young Japanese artist, whom the philosopher’s essay inspired to a sculpture and several drawings, for this truly irrelevant information). And there is a manga comic called Full Metal Alchemist, playing with the European tradition in a trashy Japanese way.

Our contemporary artists don’t seek to explain, but to visualize, to illustrate, in different ways. Take Natasche Sonnenschein and her painting of three overlapping circles. If you are familiar with the mysteries, you can probably tell what it’s about. But there will always remain a gap between the believer creating cult objects and the artist appropriating signs from an outsider perspective. Not least for publicity reasons, they’ve included some big names with Jeff Koons – a pink Balloon Venus -, and Anselm Kiefer – a stone book mapping the stars (Totality of the Stars) to read nature like God’s book, and potentially add some notes. Additionally, and at about the same auction value as those two, there’s the world’s blingiest gold coin, a 1 Million Canadian Big Maple Leaf coined in 2007. ... Or actually, it was supposed to be there, had it not been stolen from another Berlin institution lately. Now all we see of it is a photograph, but maybe you can try and create your own, all you need is that philosopher’s stone (come on, hang in there, I’m sure you’ll make it...). To assist you in your endeavours, the catalogue comes in a box with hundreds of cards to play along, or learn by heart. Arrange the exhibition’s elements, and play at alchemist.

If you prefer to start with something easier than making gold, you could give Kulturforum’s “Alchemist Kitchen” a try, a lab mainly targeted at children, but open to adult audiences also. Members of the press got a pack of cool aid for free, with a great example of misplaced sponsoring: It carries the label of an energy supplier known for operating nuclear power plants, and you would not drink anything related to nuclear power plants, or would you?

I did. It was ok, I guess. Kind of chemical, with a stingy smell remotely reminiscent of raspberries, and sugar, and burned plastic; despite the “organic” ingredient list (there’s also “natural flavours” indicated, so whatever...). I did not spice it with quicksilver. And so far, my intestines have not started to produce gold. But my neighbour seems to have grown a curious pair of purple wings. And three heads; then, there’s that voice that keeps telling me... no, just kidding.

Alchemy. The Great Art, 06 April-23 July 2017, Kulturforum

World of Arts Magazine - Contemporary Art Criticism

Comments