Will the Builder, and a Draughtsman

- Christian Hain

- Dec 15, 2017

- 5 min read

Updated: Mar 25, 2020

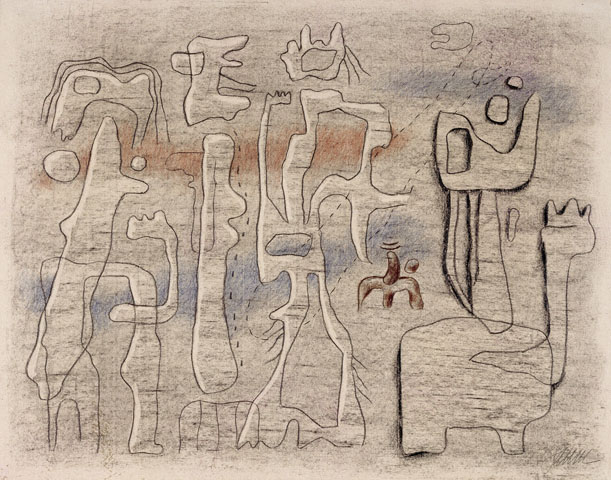

(Berlin.) For a change, the latest exhibition at Kupferstichkabinett does not celebrate an artist’s anniversary or some kind of memorial. There’s no Willi Baumeister year, and not even a private collector eager to show off, and valorize, his treasures. No, this is “just” an ordinary curator’s project. And it’s great. Willi Baumeister - the surname literally translates to “Master Builder” - might be considered the counter draft to Hans Hartung. Both were eminent German abstract painters active in the first half of the 20th Century, but while Hartung emigrated to France, and today is still more famous and revered abroad (no Parisian art fair without an uber-expensive Hartung), Baumeister chose to stay at home, in “inner emigration”, when his works were defamed as degenerate (“entartete Kunst”), he was stripped of his professorship at Frankfurt University, and could no longer exhibit in public. Yet, Willi Baumeister kept in touch with the international - and at the time that meant mostly: the French, and this still means today: the Parisian - art scene, being friends with Fernand Léger, Amedeo Ozenfant, Le Corbusier, among others, and trying to smuggle works to Jeanne Bucher Gallery. Baumeister’s post war fame remains a little more limited to his native country, his success more domestic. However, Hartung is one of the (many) artists, Baumeister is frequently compared to, and this latest show makes no exception. Kupferstichkabinett owns some drawings, but not enough for an exhibition, thus once having taken the decision to focus on that technique - their line of work, after all -, the museum also invited other, mostly public, collections, to an overwhelming result. Patrons now may admire almost eighty works of paper in total, small to midsize. Most were intended as drawings from the start, and not preparatory to any oil on canvas. If you don’t care, or are unsure about dates and epochs of art history, you can easily suspect, Willi Baumeister was a sponge, soaking up everything he saw in art and else, and successively releasing it. Then you check, and realize, he often stood at the very centre of those styles and movements. There’s so much in his work, there was no way, KuStiKa could forego the temptation to create immediate comparisons by hanging his works next to other artist’s. Curators not even felt a need to create thematic chapters, but chose a most classic, chronological, exhibition design instead, that covers almost half a century, from 1908 to 1955. Willi Baumeister is art history, (re-)building it. The earliest compositions already appear geometric, yes indeed: architectural, in some cases, nomen est omen. The very first drawings he acknowledged and esteemed enough to have them included in his catalogue raisonné, a scene with cats and dogs, a billiard table, date from 1908, when the artist was aged nineteen. They reveal an early interest in cutting reality down to forms, lines and movement. This said, almost throughout his entire career, Willi Baumeister would stick to some residues of figurative painting. If only you look close enough, parts emerge to equal a familiar form, most often the human frame, and even modest circles are not merely meant as such, but add elements of the concrete world, trivial like sports equipment, tennis rackets and footballs. This is no pure abstraction, or only as a verb: “abstractifying” forms. In his 1945 book The Unknown in Art, Baumeister characterized his trade not as aiming for a duplicate of nature, but a creation in its own right. At least in coded form, he would never let go of all ties to that first, original, creation. This re-construction, as opposed to mere deconstruction, of given forms, is one reason why he seems so close to Cubism and Surrealism (the latter mostly for formal/stylistical, not theoretical, reasons), in works like Image T 21, 1922, Handball Player III, 1935, With Dark Forms, 1938, or Dialogue with Montage, 1944. Like every decent Cubist artist, Baumeister fell in love with Primitivism, with stone paintings and African art. Not exactly pc (thus once again despicable/“degenerate” to our modern standards), he perceived Africa’s noble savages as primitive and different. Archaic Scene Coloured, 1944, Movement III, 1949, one is named African Games, drawn in 1943/4, seven years after another “inner émigré”, Ernst Jünger, published the eponymous autobiographical novel. They were of the same generation, but nothing is known about any personal contacts in wartime or after. During these years, however, Willi Baumeister developed a thorough interest in literature. Several works allude to German national poet Goethe, such the surrealist Eidos, 1939, or Faust, Hovering, 1953, that latter perhaps a little more easily decipherable, the most picturing a scene, condensing the plot. Usually it’s just free associations. More examples include Wilde’s Salome, illustrations for a German language edition of Shakespeare’s Tempest (easy: those spirits, or Caliban, could hide behind every dot or form), while Sumeric Legends (1947) and Gilgamesh (1954) combine both interests. Is that a train approaching in the top right corner of Group of Figures with Colour Zones, 1943? These series (on Africa, Primitivism, literature) foreshadow later artists from Pollock to Basquiat and Hering, yes, graffiti even (Movement III, 1949); Kupferstichkabinett adds a (really small) Pollock, and A.R. Penck.

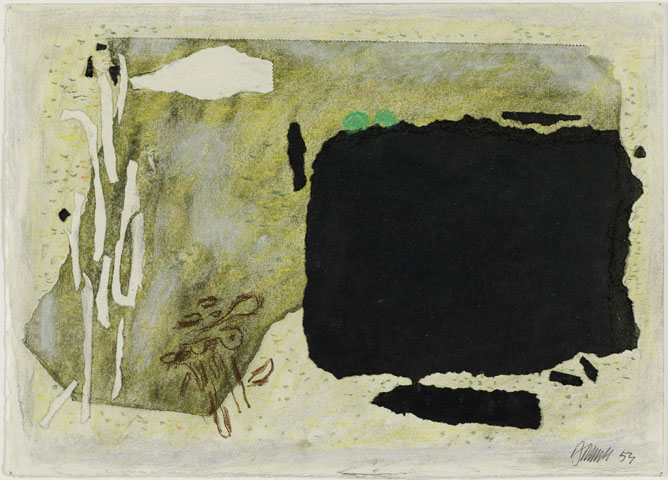

There are more aspects to Baumeister’s career. Take Apoll, 1922, and you see Duchamp’s Nu descendant un escalier (1912), Futurism, androids, man-machines. If Metropolis had not been released five years later, I’d have said, Baumeister portrayed robot Maria; it actually seems the other way round - Lang must have known this work. Another Depiction of Apollo (“after Dürer”, you might add), 1921, appears much more geometrical, and actually exists in two versions, one coloured with pencil, the other monochrome china ink. This must be the article with the most namedropping since long, but Little Flame Figure (1930) suggests Frida Kahlo's famous Broken Coloumn (1944), don’t you think? The metal corset in his case copies the effect of fire burning through paper – something artists like Yves Klein would literally do years later, taking contemporary art that one step further. Baumeister’s Dancers and Runners (several of each in 1934) announce the same artist (i.e. Klein), and even more so Matisse with Jazz. The other first work – actually the last in show, but if you follow your track and field instincts and turn right at the start: the first, belongs to the few total abstractions from the last period of Baumeister’s career: Montaru with Gondola, 1954. Like ARU with Dots, 1955, and Cosmic Gesture, 1950, it’s indeed not Joan Miro, but Willi Baumeister. The one Miro that’s here, hails from another series/and style. In those titles, Baumeister by the way developed a more or less secret laguage, where Mont-uri meant white, and -aru black. Among the few neglects of an otherwise excellent exhibition counts the omission of Mondrian. There are definitely similarities, it would have been interesting to compare the Dutchman’s mathematically squared compositions to Baumeister. On the upside, there’s Max Ernst, Juan Gris, Oskar Schlemmer, and they could have added so many more, we won’t complain... It needs to be said though, comparisons do not always prove favourable for the main protagonist. So Baumeister’s The Painter with Painting, 1924, next to Picasso’s Man with Dog, 1914. Baumeister’s lines appear more thickly drawn, less fluent, more laboured, stricter, less floating, harmonic and natural. But then again: Who could ever hold his own against Pablo? At some other point, you might think, “Wow, that must be the most original, by far the best work, around here” ... (sees label) ..., “wait,... ok, ‘tis El Lissitzky”... Willi Baumeister was a child of his time, maybe the most innovative, and energetic era of all art history, and he profited much from it. Willi Baumeister. The Draughtsman. Figurative and Abstract Art on Paper, 9 December 2017-8 April 2018, Kupferstichkabinett World of Arts Magazine – Contemporary Art Criticism

Comments