Viva El Loco: Some thoughts on Salvador Dali at Centre Pompidou

- (first published on artlifemagazine.com)

- Dec 13, 2012

- 5 min read

Updated: Mar 25, 2020

Paris - Dali, "Tout Paris" is talking about Dali these days. The Centre Pompidou is virtually closed for any other activity as the huge waiting line at the main entrance means you'd have to queue for two hours in the cold even if you only wanted to visit the museum's permanent collection (which is in fact completely deserted). Of course, having people waiting outside the building does some good publicity too, so why organise it differently...

Once again an art exhibition turned event.

Salvador Dali is a familiar name, being a tourist you won't take any risk with a visit, it would even be more shameful to come home and justify your not having gone there. This is confirmed art ("crazy but not too contemporary"); everybody is allowed (and expected) to like it.

Dali was a media phenomenon in his lifetime and for this reason not always cheered by art historians. For many years his success has been watched suspiciously, he has almost been regarded as a spooky version of Chagall. Can a new retrospective at one of the world's leading art institutions rescue him from these lows?

The earliest works presented here are self-portraits in either classic or cubist manner from the early 1920s. Some time later Dali enlarged his focus to his close family circle with portraits of his father and sister. You can recognize his talent, his technical skills right from the start, and all he needed for his public breakthrough was a personal style, which he developed shortly afterwards when becoming surrealist. Surrealism lifted Dali to the stardom he so much desired. No doubt, he was also a master of self-dramatization, the first Hirst. Based on Bohemian myths Dali used eccentric spectacle to get noticed and create a show around him, he branded himself a genius and his persistent popularity proves how well it worked out.

Both in technique and content, Dali found his own ways. This surely is one of the reasons for the enduring success: everybody may feel an expert in recognizing his works. Those thin lines, in-between drawing and painting, Dali is always Dali, a trademark. And even when it gets gory, and it quite often does, these are still beautiful pictures with peaceful pastel colours.

Dali's early occupation with cubism is helpful to further understand his approach. Picasso and Braque had proved you do not need to show every part in order to create a whole, and Dali continued in the line of deconstruction. With Dali there are only details left, different scenes are deconstructed and rebuilt not just in changed order, but in enigmatic fantasies.

Other major influences were Hieronymus Bosch and outsider art, which was not yet known by this name. Dali copied the artistic manner of mentally deranged persons with his unique skills. Often is said he created a world of dreams, but honestly, did you ever have dreams like these? Dreams usually present objects, persons, memories and episodes in more or less arbitrary succession, but most people dream of a watch as a watch and not of a watch floating over a fence like a fried egg (and if you do, you might have serious issues). We generally lack the creativity to dream of unseen monsters, most people's dreams are not that visually innovative. Hallucinations are.

The main question about Dali is, had he or had he not mental troubles beyond the evident megalomania? Is his "outsider art" (of course he was all but an outsider of the art market) authentic or refined?

Most Experts answer, he knew exactly what he did and only feinted delusion. This actually corresponds to what he said himself: "The only difference between me and a madman is that I am not mad".

His works are well calculated; Dali rationally decided to paint visions that he did not have in the sense of a believer (/madman /drug user). He used this peculiar language to create metaphors.

In Dali's paranoiac-critical method one thing does not mean but refers to another - you don't need to be an expert in psychology to know that so much is true for many dreams.

What we see are images of, allegories for and mental associations to classic topics of (pseudo-) philosophy: sex, time, suffering and death.

The paranoiac-critical method was based on the hypothesis of irrational mental bridges between images and ideas, the contemplation of one was supposed to evoke another. The system, that seems to be strongly dependant on cultural upbringing, still is conventional, even if the convention is not formulated consciously. It basically means there is an iconography, and iconography has always been understood automatically by the initiated.

The true innovation that makes Dali's special is the presentation of these signs. His scenes are fantastic; the different parts are unrelated one to the other. In classic art we habitually have two layers, a seemingly simple scene hides a multitude of signifying details. Even if you know nothing about its iconography, you will comprehend the outer appearance of an old master's painting. Dali on the contrary hides his riddles in a big one. There is not a secret language disguised in an obvious scene, but only secrecy as such - or riddles behind a riddle. Dali simply points to the details waiting for decryption, he refuses to resolve, or to hide, his secret messages in outer simplicity. His compositions do not show something apparently simple; they make the mystery apparent.

The images don't tell a story, they stand for themselves, though every detail on the canvas has a - or refers to - a meaning, the composition as a whole scarcely has. Dali's arrangement of signs does not create a coherent impression, the equation has no result, he tells aloud there is iconography - and nothing else. Certainly this also played into his cards in the struggle for fame as the Great Illusionist.

A big success at Centre Pompidou is a room interior that on a mirror reveals a huge female face (the actress "Mae West", 1934); visitors may sit down on a red couch (the "lips") and take a photograph of themselves. Like all surrealists Dali liked optical plays, pictures that change their appearance with the angle of view. Certainly, these magic tricks are nice, but well... it gets boring rather quick, don't you think?

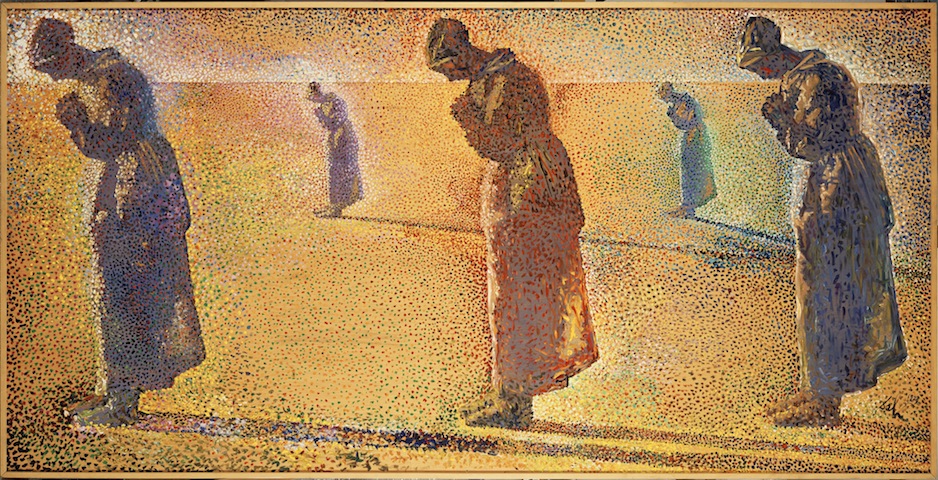

The bigger surprise are a pointilist painting, "Aurore, Midi, Couchant et Crepuscule" (1979) and some Warhol copies - the most interesting being "Autoportrait", 1972, with the portraits of Mao and Marilyn mixed in one - when Dali left his usual ways.

Personally I miss the humour in his work. Wherever there is it is involuntary. Like the recording at the very start of the show when we hear Dali talk French with his heavy Spanish accent and the very word "TraumaDIIISSme" (Traumatism) brings a broad smile on every face (at least it made me smile and French is not even my mother tongue). Or take a look at the film documentations of several performances during the 1970s with the artist and assistants trying to look extremely meaningful when for example pushing a piano into the ocean.

It is impossible to talk about Dali without mentioning "Un Chien Andalou" ("The Andalusian Dog", 1929), the legendary film coproduced with Luis Buñuel. If you are searching for in this exhibition: Right at the start in the left corner behind the entrance, maybe you have to wait a while as there are several films playing on the same screen.

It is a true art film in the strictest sense - neither documentary nor narrative, it does not follow any traditional form. "Un Chien Andalou" is a visual experience most close to Dali's paintings - a disturbing, yet aesthetic, collection of signs.

"Dali", Centre Pompidou, 21 November 2012-25 March 2013

Comments