Visions, woodcuts and a Rhino: Albrecht Dürer and William Kentridge at Kulturforum

- Christian Hain

- Feb 12, 2016

- 6 min read

Updated: Mar 24, 2020

(Berlin.) Kulturforum is the name given to a cultural hotchpotch some hundred metres off Potsdamer Platz. There, in a no man’s land adjoining Tiergarten park, mid-19th Century St. Matthew Church is under siege by the Berlin Philharmonic Hall, the Picture Gallery, the Kupferstichkabinett (old drawings and prints), a library, and much, too much, more uninspired architecture. For over fifty years city planners and architects have been desperately trying to improve the place, but still to no avail. The Double Vision show with works of Albrecht Dürer and William Kentridge takes place in the main building that otherwise serves as a reception hall and ticket office.

Now, do you remember that lone terrorist who once entered a poorly visited museum, hiding an assault rifle and suicide belt above the clothes, but under a thin jacket? When being asked to leave the jacket at the cloakroom, s/he turned around, and quietly went home, realizing that all evil designs were foiled. No? Well, neither do we. But people at Kulturforum imagine life to be that way, and will ask you to deposit your belongings “for security reasons”. It won’t put you in the right mood for the show. Which is a pity.

Albrecht Dürer, a serious contender for one of the top three draughtsmen in history (we would never, in no context, say “of all times”, as we don’t know the future) meets William Kentridge, lesser known to people not into art, yet arguably one of today’s greatest artists. As an introduction, Kulturforum holds a very inartistic lesson on vision and “conceptual contextualism”, but don’t let this scare you, and simply proceed to the art. Both artists are/were not only visionaries, but share(d) an interest in (the science of) vision; they directly address(ed) the creation of perspective. Albrecht Dürer frequently depicted the art of creating, the artist “arting”, in works like The Draughtsman of the Female Model / ... of the jug /... of the lute. He was seeking to teach, to explain the magic, and maybe even to downplay his own genius. Yet, we should always remember, that he would long be forgotten, if this would have been all, if he had only had the technique, but not the gift: All teachings won’t help you, if you simply cannot draw a straight line. - Dürer himself is sometimes quoted with words: "One man may sketch something with his pen on half a sheet of paper in one day, or may cut it into a tiny piece of wood with his little iron, and it turns out to be better and more artistic than another's work at which its author labours with the utmost diligence for a whole year."

A universally learned Humanist, Albrecht Dürer was an expert in mathematics and geometry; several copies of his book Underweysung der Messung (Instruction in Measuring, 1525) are on display at Kulturforum. The second edition of 1538 includes that uber-famous woodcut of an artist drawing in a grid what his eyes perceive behind a glass plate (a naked female that is, and we won’t talk much about the artist’s looks, or the erect instrument between his arms – the work is not about drawing techniques alone). The idea is to meticulously copy nature, to cut it in pieces, and transfer them on paper. But we know, that vision depends much on mental constructions, on error and deceit. Film is an example, three-dimensional images another. William Kentridge “creates” them with the help of special glasses to behold two of his drawings simultaneously. It feels kind of like a visit to the ophthalmologist’s, but right eye and left eye trick the mind into seeing one image with depth. Some of these drawings also hang framed on the wall, without glasses attached, and we wonder how Kentridge’s gallery is offering them (maybe you could use your own glasses, those that you've stolen at the cinema lately?).

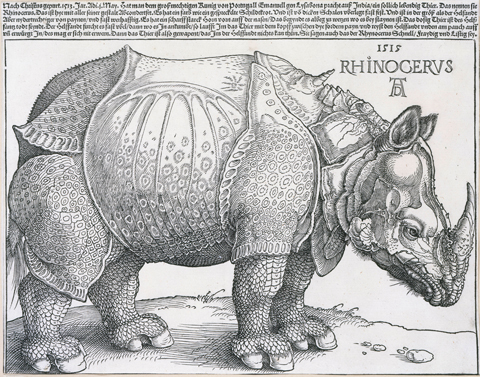

Dürer was also talking about himself and his peers, when painting Saint Hieronymus in his Study (1492) surrounded with books in Latin, Greek and Hebrew, plus a poodle to whom he’s giving a manicure. (Scholars know, the poodle is a lion, an animal that can stand for many things - our dictionary of symbols lists, among others: force, reason, virility, Christ and the devil). The same pet makes a return in Saint Hieronymus in the Desert, but this time with a decidedly human face. Apart from bible stories, Dürer illustrated natural science textbooks in a very different style: cold, academic, illustration. It’s true, that his animals look realistic, magnificent in detail, but also dead, detached, “scientific”. There lies a huge difference between his paintings – the well-known hare for instance (not in this show) and his engravings – The Rhinoceros (in the show). To us, who we’ve seen rhinos at least in zoos and on Discovery channel, this one looks more like the cross between an armadillo, Hannibal’s war elephants and an overweight unicorn. It’s wearing armour. To be fair, Dürer only ever knew another artist’s sketch of a taxidermied rhino. Inspired by this legendary work of art, William Kentridge created Sketches for Three Rhinos (2005). His creatures “live”, they are not static illustrations, less academic, but so much more natural - warmer, more elegant, less dissecting. Especially when they sit in front of a dog’s food bowl. If you hear a visitor cry “Soo cute”, she will not be beholding a Dürer’s work. This is, of course, a question of intention, but it might also be connected to a media, Dürer could not know, i.e. film. William Kentridge works a lot with film, he creates animated movies from his drawings, and if his rhinos look inspirited, it could well be for our association with moving Disney beasts. A photo of Kentridge’s studio appears like taken at a film set (or a photo shooting). Kulturforum also shows a drawing for Felix in Exile (1994) (YouTube is your friend), other films we may even watch here: Drawing lessons with its magic tricks is far from any utile “Underweysung” ("Ynstruction").

William Kentridge’s paper cuts, that are not actually cut out, but blackened shapes on paper, again convey that sense of movement that Dürer’s engravings lack. Dürer’s images are more static, harder, stricter, yes: more German. Even if you compare his drawing style with his contemporary da Vinci’s, the latter’s undoubtedly seems more animated. (Kentridge’s Living Language (Cat), 1999, has a cat lying round like a snake on a record, and the label doesn’t read "Cat Stevens", but “Italian Language Course”, in mirror writing.) Please don’t get us wrong, obviously William Kentridge is not on the same level of genius as the Renaissance giants, far from it, but this exhibition shows some changes in art history over five centuries. Simplification adds naturalness.

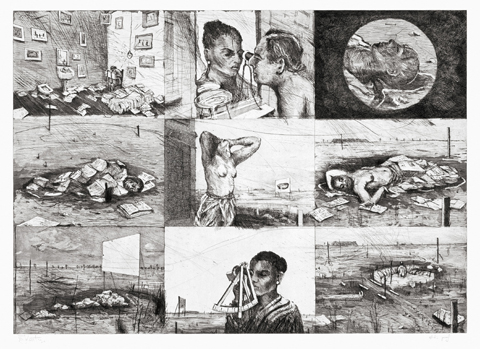

What else? There’s Dürer’s wall high comic strip Die Ehrenpforte (The Gate of Honour), and some large panels of Kentridge’s. Several painting by both artists can be seen through magnifying glasses that we move about on rails. Amidst your own reflection you may thus inspect the details of Kentridge’s series Pit (1979) from a time when he wanted to be Francis Bacon. And Kulturforum decided to compare one of Kentridge’s scenes for Jane Taylor‘s play Ubu Tells the Truth (loosely based on Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi) to Albrecht Dürer’s Melencolia I. As Robert Burton wrote in 1621: ”... and as Albertus Durer paints melancholy, like a sad woman leaning on her arm with fixed looks, neglected habit, &c., held therefore by some proud, soft, sottish, or half-mad, as the Abderites esteemed of Democritus: and yet of a deep reach, excellent apprehension, judicious, wise, and witty: ...” Nothing much to add here.

Finally, some words on the exhibition design: William Kentridge’s Plan d’atelier (Studio Plan), a sort of stylized board game, is not only hanging on a wall, but covers the floor, in form of a much enlarged copy. In it you’ll read authentic artists’ thoughts like “Insupportable weight of eyelids”, "An echo of emptiness”, “6 1/2 minutes of sleep”, and fittingly there is a large sofa-bed standing in the middle of the show, with cushions. There are also closed vitrines with catalogues and books on the artists(?!). And a long table with more catalogues, books – including several on exhibition design – and folders; the books are glued on wooden boards to prevent you from “borrowing” them. A large mirror behind the table serves that same purpose. In the entrance room, you’ll find a wall covered with self praise, i.e. articles on the exhibition (we guess, this one won’t make it there). All in all, Double Vision at Kulturforum is worth a visit.

"See them survey their limbs by Dürer's rules,

Of all beau-kind the best proportioned fools!"

(Pope, The Fourth Satire of Dr. John Donne Versified, 1733)

Double Vision, 20 November 2015-06 March 2016, Kulturforum Berlin

Comments