Tuttle’s Texts and Textiles Take Tate’s Turbine Hall, Whitechapel too

- (first published on artlifemagazine.com)

- Nov 17, 2014

- 6 min read

Updated: Mar 24, 2020

(London.) Lately focusing on Paris, ArtLife Magazine still leaves France from time to time, for example to see what’s going on in the UK. If you’re a EU citizen, you never know how much longer you may profit from - comparatively - easy border crossing, but so far nothing has changed: Britain is still in Europe (and Scotland is still in Britain).

London is a city of wonders, each time we Continentals get there, we discover something new, something strange and disturbing. To Parisian eyes, even Father Thames can be a revolting sight when the low tide lays bare his dirty sleeves of sand. His stonen corset sits less tight than the Seine’s, despite both of them have been turned into a channel centuries ago. Step on the grass, nature’s wearing less make-up, trees and flowers may grow unfenced (quel horreur!). Just when you think you got used to walking on the wrong side, and avoid tripping down an oncoming escalator to take the one on the left instead, you read a sign on this same escalator telling you to “Stand on the right.” On top of all this think free museum admission, and you’ll get an idea of the dangers every trip to London poses for Parisian citizens.

But art. Thanks to this world’s oligarchs, sheiks and Chinese, London has become a primary market place for contemporary art. Apart from the bunch of commercial galleries and auction houses, the city offers some of the best museums and public galleries (with tears in our eyes we can only repeat: for free. Take that, Louvre, Pompidou and all the rest of you greedy ba----ds.) But of course, you know all of this.

American texter and textilist Richard Tuttle is the latest artist to invest Tate’s Turbine Hall. The Turbine Hall is a spectacular venue, but, to be fair, not quite as spectacular as the Grand Palais.

The first impression of I don’t know. The Weave of Textile Language, Tuttle’s monumental sculpture says: “Aircraft rear stuck in candyfloss, not totally unreminiscent of Christo and Jeanne-Claude”. Other associations might be a whale’s fin or, if you prefer, the rear spoiler on that lad’s 1990s’ Vauxhall Omega.

On its “wings”, the wooden structure is left bare with some yellow rags here and there, whereas the middle part is entirely wrapped up in red cotton. Walking around, descending the stairs to the basement and looking up, the impression changes to “fluffy cushions tortured with a stapler”. A closer inspection reveals tiny rhombuses, like diamonds in a deck of playing cards, painted on the cloth. Stepping back we finally read the letter “T”. The letter leads to words that might or might not have something to do with the sculpture: A tower of textiles, and that middle part, doesn’t it resemble a tree trunk? Not claiming the artist intended any of this, we dream away of a cup of tea under the nearby Tower Bridge over the river Thames, and, of course, it’s Mr. Tuttle invited to the Tate (kind of reassuring that the exhibition is not sponsored by a German automaker with the suitably named car model).

This “T”, as what we have now identified it, measures “over 12m” in height, much more in width, and floats suspended in the air. Despite its magnitude, and thanks to the warm colours, it conveys a sense of fragility that is confirmed by the interdiction to touch the “trunk”, lest it all fall to pieces. As a whole, it’s impressive, and makes the visitor curious about the rest of Richard Tuttle’s show.

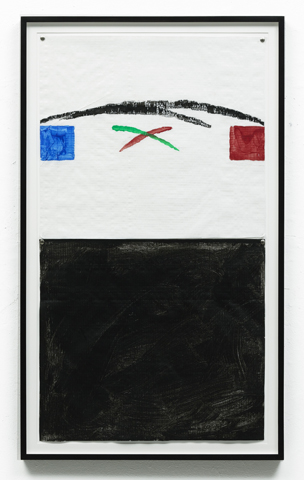

Only four tube stations away at Whitechapel Gallery, this second part promises to offer deeper insights into the artist’s work. For us tourists, it would have been great to find it named “Rick the Knitter”, or something, in true Whitechapel spirit. Instead, the exhibition carries the same title as the installation: I don’t know. The weave of Textile Language. Here, the art is smaller, mostly framed and hanging on the walls. Richard Tuttle creates images from unusual materials, cotton, wool, fibre, a tad of metal, and wood. Sometimes it’s only threads on the floor or wires on the wall. The poetic harmony of raw materials woven to abstract forms is unexpected. Maybe this is minimalist, but it’s a warm, a deeply human, minimalism.

It doesn’t quite come out on photos (it really doesn’t), but all of this looks very “organic”. Tuttle brings the materials to a raw, a natural, state where they look themselves again. Not that you could smell the sheep (or petrol) that once started the production chain, but the matter seems reverted to its origins and elevated to art at the same time. This is a use of textiles that has nothing to do with fashion, is the exact opposite even. Richard Tuttle’s works seem to breath a vital force.

Textiles are a human thing, a symbol of culture just like art, intended to hide the truth. And yet, freed from function we may rediscover a purity that was thought forever lost. A common resource best known in processed, in cultivated, form gets transformed by a reduction to its self. It all points to abstract painting too, and it takes a second look to recognize the few genuine paintings (water colours). Tuttle has the power to make anything look like textiles, and textiles not as such. Even paper seems returned to its textile state, papyrus. Those little staples reappear, adding a dose of violence and DIY appeal; too much perfection can be fatal for art.

Richard Tuttle is surely the right artist to feature in our Tale of Two Cities. His threads are less reminiscent of the weaving fates, but to stay Greek, Ariadne’s thread leads us to another world, a better one indeed. Whilst the text written over some works is undecipherable, most are accompanied by quotes of the artist, little poems that talk about the piece, but speak of much more. Only one example:

“The woven and the unwoven/

Seeing knows no rules. The/

Textile is always free of itself/

Because it is laid on thread/

Yes, what is not thread? – Mind/

Or Matter?”

(Clutter, 2008-12)

Sounds deep. A Whitechapel’s explanatory text says, “text and textile share the same root but not the same stem”. Sounds clever.

We’re not sure, if these works are truly intended to be read, but even in pure being they are captivating. Some artists can only do small format, whilst others need to be massive. With this double show, Richard Tuttle proves he can excel in both.

When we were visiting in early November, the whole city seemed to continue the exhibition: if an artist has designed those clip-on poppy seeds, it could well have been Richard Tuttle. Once again, for us foreigners: these are not to commemorate the Opium Wars, but all British soldiers who ever have "perished on the fields of glory” (but who were in no case connected to the "evil imperial past"; political correctness is a big issue on the island these days).

Once at Whitechapel Gallery, you should also visit the last days of Kader Attia's exhibition Continuum of Repair: The Light of Jacob’s Ladder. The Algerian artist filled a room with books and artefacts of various origins – French, German, Arabic - to question the concept of knowledge and creation. Where does science end and art begin, are not research and classification mere “mind art”? The term “repair” is written repeatedly under the ceiling of an adjoining room, and the artist states: “The biggest illusion of the Human Mind is probably the one on which Man has built himself: the idea that he invents something, when all he does is repair”. (Failing to) Repair a perfect world that is broken, then repair ourselves to another one.

In the end, the most annoying part of every trip to London is the thought, “would be nice living here”, followed by the realization that about half the earth’s population has had the same idea. A circumstance that helped lift the rents to the standards of Monte Carlo or St Moritz, so everybody you’ll meet in the streets is either a tourist, a millionaire, or lives three hours from work. And when those numbers do finally come (they will, they have to), would you not rather move to Monte Carlo or St Moritz (the sun, the beaches/the mountains, - the no-taxes)?

Richard Tuttle, "I Don’t Know. The Weave of Textile Language",

Tate Modern Turbine Hall, 14 October 2014-06 April 2015

Whitechapel Gallery, 14 October-14 December

Kader Attia, "Continuum of Repair: The Light of Jacob’s Ladder", 26 November 2013-23 November 2014

Comments