The Reality of a Dream, Surrealist Objectivity or Objective Surrealism at Scharf-Gerstenberg

- Christian Hain

- Oct 21, 2016

- 4 min read

Updated: Mar 24, 2020

(Berlin.) Another day, another private collection in Berlin, and a Mr. Scharf-Gerstenberg bathing in the glory of his art; or so you would think.

It’s a bit more complicated though: In the beginning, there was Otto Gerstenberg (1848-1935), collecting big in the early 20th Century. His daughter Margarethe Scharf pursued the same hobby until much got taken away for a battlefield souvenir by Russian soldiers in 1945. Today, you need to travel to St Petersburg to see those works, among them Renoir’s Dans le jardin and Degas’ Place de la concorde. But undeterred, Gerstenberg’s grandson Dieter Scharf carried on the family tradition - they had made their money in the insurance business, and kept it together after the war -, and shortly before his death in 2001 lent a lot, though not all, to Berlin’s federal museums who show this part of the collection in the former Museum for Egyptian art. The building's past shows not least in a decorative Egyptian temple gate at the entrance - is this a nod to art plunder, a cheeky statement on that Russian affair?

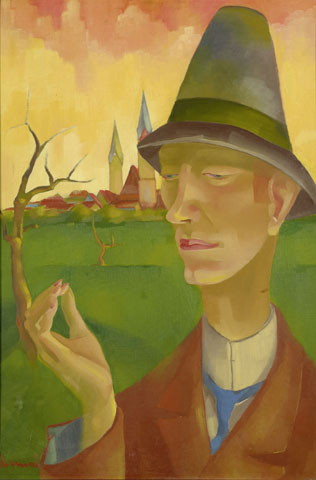

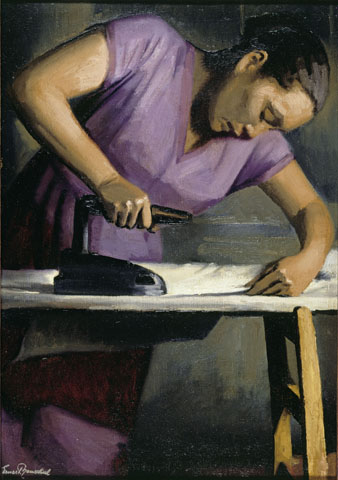

On a rainy night in early October, and it has hardly stopped raining for a minute since, SG Collection celebrated the opening of Surreal Objectivity. The opening crowd was more distinguished than usual with senior citizens sipping wine (the bar ran out of stock about an hour before the event ended), many of whom looked like they have a work or two of the show’s artists decorating their bedroom. Surreal Objectivity brings together New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit - "New Matter-of-Factness", art historians still quarrel about the best translation) and Surrealism, two movements en vogue almost a century ago. The idea is that New Objectivity, initially a reaction to Expressionism shifting focus to the painter’s vision that sought to depict the “objective” world as it is, increasingly expressed inner tensions not of the painter but the painted, and in this approached Surrealism’s obsession with dreams and the language of the soul, the sub- or unconscious. Sometimes, New Objectivists heightened their objectivity to caricature and grotesque exaggeration to express objective tensions in the “real world”. Realist nightmares are not surrealist but that much be granted: the results can look similar.

Both movements dealt with contemporary psychology laying bare the soul, but what exactly (/objectively) is objective, and what a judgement? In 1904, German sociologist Max Weber had called for an objective science, for “Werturteilsfreiheit” (“Devoid-of-value-judgement-ness”), comparable to that journalistic distinction between report – what happened? - and commentary – what shall I make of it? There is a large variety in New Objectivity, different interpretations of giving an objective account translate to different styles. New wings objectively quarrelled, the ones – the “Verists” - aimed at depicting social tensions and ugly facts, the others – the “Classicists” – at meta-temporal banality or a mix of fact and fantasy – Magic Realism in its visual arts shape. Ultimately, this means you’ll see “aplat” painting and the vector graphics of Georg Schrimpf who was sort of a premature Hopper, but also more elegantly executed lines.

Between the well known Dix and Schlemmer, a lot of artists you’ve never heard of without being a specialist in this era of German art. New Objectivity was primarily that: a German art, not an international movement like Surrealism, the term itself should be warning enough: the two “ch”s in Neue Sachlichkeit are not pronounced the same, and none of them like the “ck”. Henri Rousseau is the best known not German New Objectivist here, and he is a special case in art history. His Beauty and the Beast shows objectively what Victor Hugo left to imagination, it's less Disney and more like that donkey show in Tijuana you can never unsee.

The home side is overrepresented, with about one Surrealist work for ten Objectivists. There is, however, a Dali - a real one, beside fakes from Edgar Ende -, one or two Ernsts, a de Chirico, and even an early Magritte. Most close to each other, and an excellent curatorial choice, are Max Ernst’s Surrealist abstract Mussel Landscape (1928) and Willy Kriegel’s Objectivist Still Life with Mussels (1931). Ernst Schütte’s (any relation to today’s Thomas Schütte?) Tulips seem almost Futurist, and then, there’s Heinrich Ehnsen who did not like My (i.e. his) Children very much. Objectivity is a complicated thing, in painting as everywhere else. Once again: The painters of Neue Sachlichkeit sought to show what is. This, of course is a commonplace of what most painters most of the times told. Or what has been imagined about painters all the time, and there’s always interpretation involved. “The greatest portrait painters have painted both, man and the intention of his soul; Rembrandt and El Greco; it’s only the second-rates who’ve only painted man. That picture (...) Well, the drawing’s alright and so’s the modelling alright, but just conventional; it ought to be drawn and modelled so that you know the girl’s a lousy slut.” (from W. Somerset Maugham, On Human Bondage, written in 1915). But back to Ehnsen’s children: Either he hated them, and tried to image-ine their rotten character, or in case this is about visual objectivity, his wife must have been his sister, and so were their ancestors for quite some generations back.

Finally, August Sander’s photographs rather express a statistical type than objectively given individuals which seems very modern, psychologically. But maybe they are only included because EMoP (October)?

The show succeeds in making you hesitate in front of more than one work: “Surreal or Objectivist?”, in this being reminiscent of another multistyle show in Berlin last year. Fine for a rainy day.

Surreale Sachlichkeit, 13 October 2016-23 April 2017, Sammlung Scharf-Gerstenberg

World of Arts Magazine - contemporary art criticism

Comments