The Other One: Georges Braque, Grand Palais Paris

- (first published on artlifemagazine.com)

- Oct 16, 2013

- 3 min read

Updated: Mar 24, 2020

(Paris.) Batman and Robin. Tarzan and Cheetah. Simon and Garfunkel. Cheney and Bush. Picasso and Braque?

Much too easily, Georges Braque is locked away in the grey box with the "sidekicks" label, joining Dr. Watson, Sancho Panza, Chewbacca, and all the other "ands". Now, a new exhibition at Grand Palais set out to rectify the stereotype, and to secure his place amongst 20th Century's leading painters. Grand Palais tells hardly anything about the famous collaboration, hardly even mentions Picasso at all, instead it presents about 250(!) works of Braque, and nobody but Braque.

Where Pablo the Genius spent his boyhood nonchalantly surpassing classical Painting, Braque took a more conventional start. After his education at Le Havre and Paris, he debuted with works in the latest Fauvist fashion (not without traces of Pointillism though). Then, one sunny afternoon in 1908, Braque decided to start the next big thing himself, and Cubism was born (that's the short version, anyway). One of plenty founding myths for 20th Century's most influential art movement tells how the term Cubism was coined by a journalist on the occasion of Georges Braque's exhibition at Kahnweiler Gallery in November 1908. Be that as it may, paintings in (pre-)Cubist style had existed for a while already, made by the usual suspects: Braque, Picasso, Gris, Léger, Metzinger, Gleizes, et al.

Cubism's main period is (more or less widely) accepted as spanning from 1907 to 1920. Grand Palais shows an excellent selection of Braque's works from this era, be it Analytical (ca.1910-ca.1912: ochre, grey, straight lines, sort of a multi-dimensional jigsaw puzzle) or Synthetic Cubism (ca. 1912/13-ca.1914/17: some curves, occasionally colors, much less recognizable motives). Naturally, Cubism cannot shock any more today, and still, these images depicting objects from different angles in "insectoid facet vision" have lost nothing of their fascination, of their inherent dynamics and energy. The longer we contemplate these works, we (imagine to) see differences to Picasso. Trying to explain the feeling, why only one and not the other could have made a particular work is much harder. It might have to do with the atmosphere. Braque seems calmer, more analytical. He definitely lacked the machismo, the brutality, also the spontaneity, the illimitable, revolutionary, genius of Picasso. His works seem more distanced, more thought out; they are painted with less testosterone and more grey matter than the Spanish Tauros'. Probably Braque felt less pressed, as he had a bit less to do in his career. Georges Braque was a great artist, a truly gifted painter, but not the all-outshining Genius of a Century; and who would blame him for that? Not us, and that's why the rest of this article won't mention Big P. any more.

From 1912-1914, Georges Braque experimented with prints and "papiers collés" ("glued papers"), uniting Collage and Cubism. In the years to come, this should be highly influential for the development of Dada, MERZ, etc. After Cubism was over, Braque continued with a return to the basics. In an almost Renaissance-ian spirit, he created Bronze horses and stone reliefs that would not appear misplaced in the Louvre's (Greek/Roman/Etruscan/etc.) Antiquity Department. Braque's fascination with antiquity also resulted in a painted interpretation of Hesiod's Theogony, a 700 BC book presenting us with the gods' genealogy. More generally, the 1920s are marked by a careful return to figurative painting in his still lifes and Nudes. The still lifes further led to interiors in the following decade. In the 1940s, the historical situation - the German occupation of France - forced the artist to retreat to the small village of Varengeville-sur-mer (exactly as faraway as it sounds; for not to say "at the back of beyond"). The Vanitas motive appears in distorted skulls between hope and despair. Braque's interior scenes can now be construed as a reassurance of the private sphere as a non-occupied zone. The last interiors shown in this exhibition belong to the Billiard series, started in 1944. Another piece of furniture, but these pool tables are broken in the middle, destroyed, unusable. A rupture with the confined home, in order to announce something new?

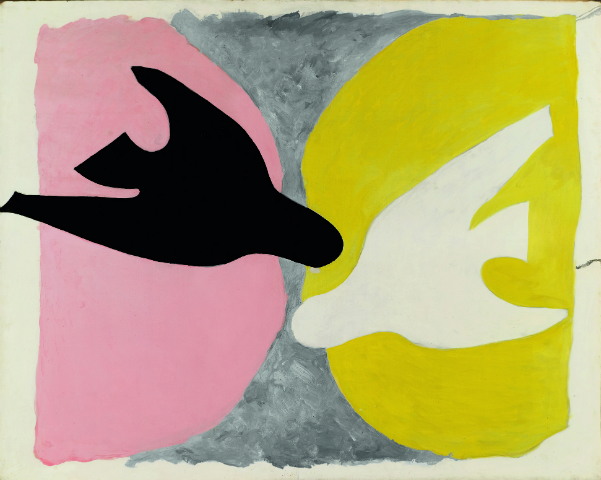

The 1950s fly away with birds. We don't want to ask, which other painter is also famous for his doves (better not). So, yes, Braque did it, too. And they fly in a unique, personal style, they really do. Non-realistically figurative, Braque remained an innovator. Long after he had nothing to prove anymore, he tried his talent in landscapes, (very) remotely reminding of van Gogh and Impressionism - a pessimist, a dark version of Impressionism. Braque's last painting belongs to this series. It shows a Sarcleuse, a weeding machine. Not a large format, he had started it in 1961, and it was left on the easel upon his death in 1963. Did he put it in a box for some time in-between?

Georges Braque, Grand Palais, Paris, 16 September 2013-06 January 2014

Comments