Sushi from Amsterdam: Van Gogh under the Influence

- (first published on artlifemagazine.com)

- Feb 5, 2013

- 4 min read

Updated: Mar 25, 2020

(Paris.) An art collector founding his own museum is nothing special these days, but an art historian doing the same seems less common. The Pinacothèque de Paris is one of these rare examples, launched in 2003 by Marc Restellini, the “enfant terrible” of the French museum scene. Since 2007 the Pinacothèque has found its permanent home in the city centre at Place Madeleine and regularly presents exhibitions of the biggest names in art history.

Apart from its small collection, the Pinacothèque shows two to three exhibitions at a time, which may or may not be related in topic. Most often these are a success in quality and business figures alike.

Currently visitors may learn something new about Vincent van Gogh's Asian inspirations and admire original Japanese wood engravings in an exhibition of Hiroshige. The experience is completed with French photographer Denis Rouvre who today is inspired by the same artists from the Land of the Rising Sun as was the Dutch painter more than a hundred years ago.

At Pinacothèque, the museum director still writes the introductory texts himself (in French, sadly there is nobody employed at Pinacothèque, who could translate any information into English, Spanish, Chinese or whatever other language) and Marc Restellini knows well about marketing guidelines, as the first phrase reads: "Vincent van Gogh is beyond a doubt the world's most famous artist."

Ok. Da Vinci? Michelangelo? Monet? Picasso? Dali? Warhol? Just saying...

Never mind, claim something loud enough and people will buy it (will they?).

Vincent van Gogh is first and foremost remembered as "that mad guy with(out) the ear" and this reputation has partly obstructed the view on his art itself. The exhibition wants to highlight a different aspect of his career, the influence of Japanese masters from the 18th and 19th century: Hokusai, Hiroshige, Utamaro, Harunobo. It traces the story how van Gogh started to collect Japanese art in the early 1880s, how he intensified this fascination via the art dealer Siegfried Bing when living in Paris from 1886 onwards and how he finally moved to Arles in 1888, in letters to his brother Theo calling the "Midi" region of France "Japan".

A number of paintings, most of them lent from Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, are presented with large panels that explain how van Gogh copied details from the Japanese masters - trees, buildings, personages etc. In order to see the original wood engravings and not only small reproductions, one has to visit the second exhibition, where Hiroshige is presented without further reference to van Gogh.

These Japanese works look basically like a mix of Brueghel, Daumier (in the caricaturesque faces) and comic strips; what distinguishes them the most from European art - by which they have in fact been influenced in the painting of perspective from the mid 18th century on - is their courage for white spaces. Large parts rest uncovered by paint, something scarcely seen in Europe before the 20th century.

The influence on van Gogh is evident and not generally known to non-experts. Who would have thought that the Good Samaritain (after Delacroix) is also "after Hiroshige"? At least there is a similar character in Voyager Descending From a Horse Close to a Restaurant on the Road to Kamakura (now that's an exact title, isn't it?) and this is no coincidence. Even his move to "Japan" (i.e. Arles) did not mean that van Gogh would stop copying from Japanese prints and take his inspiration from the actual "Japanese" (= Midi) landscape instead.

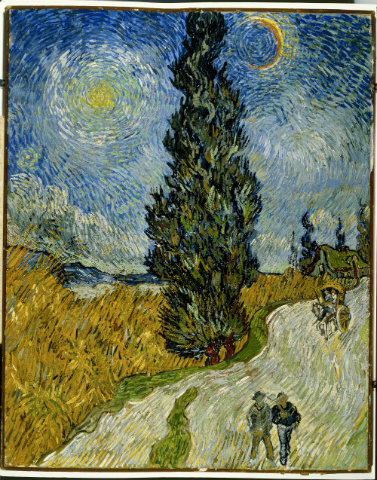

Regarding these works, one cannot help noticing how van Gogh more and more translated the Far Eastern art into his own language. Obviously these paintings belong to one of three categories: In the early years he tried to capture as much of the original spirit as possible, an example for this pure appropriation is Drawbridge in New Amsterdam from 1883. Later there are some intermediate works, that van Gogh executed partly in the original, partly in his own style and finally, in his last years (he died in 1890), he still copied details but more and more transformed the painting's total appearance - either willingly to accentuate his own artistic identity or because he could no longer restrain his tormented mind. Now the typical van Gogh style prevails and it is hardly possible to regard these paintings without thinking of the artist's inner tension and unrest. Where the Japanese prints are clear, fine drawings, precise Zen exercises in pale smooth colours, van Gogh's versions are marked by rough lines and deep thick colours, frantically spewed out over the canvas. This is not just Europe translating Bruce Lee to Bud Spencer, an adaptation to the audience's taste, but a more profound change coming from within the artist himself. Van Gogh's trembling forms reflect his state of mind, always moving in a chaotic frenzy, chronic nervousness reflected by abrupt movements of the brush on the canvas, sky and meadows are neither blue and green nor plain white but appear as unevenly curved lines. Maybe all those years van Gogh longed for the proverbial Japanese calm; sought meditative harmony as a refuge, forever unable to reach it. When van Gogh paints like van Gogh, his work is never harmonious but unsettling. And this is precisely why - despite its great efforts to show another major influence - the Pinacothèque cannot make the visitor forget the image of the madman.

The small (and free!) exhibition of French photographer Denis Rouvre bears similarities to the painter's early works. Taken in Japan after the 2011 earthquake, his pictures recreate the style of the historic landscapes before a white sky. We can only hope for Mr Rouvre that he will not continue his career - and life - in the exact same way as van Gogh.

Van Gogh - Rêves de Japon; Hiroshige; Denis Rouvre

Pinacothèque de Paris, 03 October 2012-17 March 2013

Comments