‘Straya Now for me – The National Gallery of Australia Visits me Collectors Room

- Christian Hain

- Nov 28, 2017

- 7 min read

Updated: Mar 23, 2020

(Berlin.) G’day, mate! ... Let me see, what stereotypes do we have ‘bout ‘Straya? (“‘Straya”: check - ‘Strayan slang is to ‘breviate ‘vrything.) That’s not a boomerang, that’s an artwork (“Crocodile Dundee”, check; “boomerangs”, check)! They keep crocodiles for pets, but get killed by stingrays (Steve Irwin, check). Now, to be honest, this little text you are about to read, and the exhibition it’s dealing with, do not actually concern that Australia, the white one, her majesty’s convict colony, but the other, the older, the Aboriginal, Australia (for an instant, I hesitated: Is it still ok to say “Aborigines”, has that term not been banned yet? You never know).

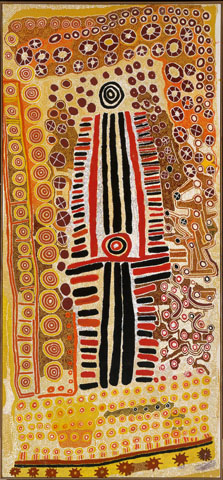

Indigenous Australia is the second instalment in a new, unofficial, exhibition series at me Collectors Room, or maybe even the second exhibition since a never officially announced change in concept. First was that Arab thing in Spring, no: autumn. For the next stop on his trip around the word without ever leaving home (/pied-à-terre in Berlin), me’s owner, and very important collector, Thomas Olbricht, MD, was back in person at the (press) opening, as usual proving impeccable taste in sneakers - no really, “whatarethose”? Australia Now is the name of a marketing campaign, few Berliners ever have heard of, the mission “to showcase Australian culture in Germany”. They don’t serve kangaroo steaks at me’s cafeteria though, nor vegemite, or cheezels. The foundation’s contribution is merely to invite the National Gallery of Australia’s Collection of Aboriginal Art for an exhibition. Even the most ignorant outsider could hardly escape the impression, relations between the National Gallery and this particular collection are complicated. The Aboriginal-Australian (you really say that?) curator Mrs. Franchesca Cubillo speaking for the museum constantly referred to “them”, and “their nation”, and “connections to their country”. But is it not “you” – not simply from a personal perspective, but: “you, Australia”? At which point we might wonder, who are the “true” Australians, and whom does the “National” Gallery represent? Just give them their self managed museum already... Let’s plunge into the action. Indigenous Australia starts with water colours, and tapestries that are none, but dried tree bark. Not bringing much knowledge of the iconography, you won’t learn much by a visit either. You perceive animals and abstract patterns, and you’d very much like to know more about the mythology, not least in the case of a man smilingly giving birth (Malawan 1 Marika, Coming of the Macassan Traders, 1964). Or what about that other guy swallowed by a snake, sort of an aboriginal Jonah? (Peter Marralwanga, Ngalyod, the Rainbow Serpent Swallowing a Woman – so it’s a woman, alright!) It's not necessarily bad not to understand a thing for a change, it will even do you good from time to time, yet nevertheless, some guidance would be welcome here. Aboriginal art and stories often do involve a snake or two. There‘s hardly a poisonous animal not living in Australia, or: hardly a non-poisonous animal living in Australia, the place where nature’s out to get you, but – and correct me, if I’m wrong: - Rainbow Snakes are not actual critters. No, they depict/symbolize/mythologize, ancestors, or even a common ancestor of all Aborigines. A lot of these paintings are ancestor portraits, akin to something we’ve seen in a whole different context lately. Most are rather recent, dating to the 1960s and ’70s, and belong to a retro movement in Aboriginal art. The technique, the meme, has been perfected throug millennia, though. Visitors admire an owl man (Alec Mingelmanganu, Wandjina, ca. 1980) and other chimaeras, while an astonishing abstract on the floor appears almost three-dimensional (Doreen Reid Nakamarra, Untitled, 2007). There’s Aborigines dancing the Haka, no wait, that’s New Zealand, my bad! (William Barak Corroboree, ca 1885), and fleeing Europeans (Tommy McRae, Meeting the white Man; also sketchbooks of the same artist, 1980, one label says “1890” but that’s probably a typo). Many conflicts between Aborigines and European migrants remain unsettled. Some Aboriginal art looks decidedly psychedelic. Pituri, the outback’s favourite plant, is reportedly most comparable to coca leaves in its effects and usage, and thus hardly responsible for this art, but I guess those didgeridoos work their magic if you listen for long enough. Visions and resulting images are not called dreams but “dreamings”, and “dreaming stories”. They include more or less coded depictions of sacred sites and ancestors, a sort of map readable only for the initiated (but so are ours, too). One is signed Paddy Jupurrurla Nelson, Kwentwentjay Jungurray Spencer and Paddy Japaljarri Sims – honestly, Aboriginal names are my second favourite, after Madagascan! With some help, even non-Aborigines can comprehend, what’s going on. The Rainbow Serpent - whose ancestor was it again? – going Godzilla on Darwin (the city!) I was told, is the fictionalization of a hurricane (or cyclone? – a storm) savaging the city in an “actual” event. - Not less true, and much more human than scientific record keeping, don’t you think? The artist, Rover Thomas (Joolama), according to anecdote once visited a contemporary art museum and asked: “Who’s that chap painting like me?”, pointing at a Rothko. It’s not the sole occasion, you discover parallels to Western art heroes. Thinking “Paul Klee” while contemplating Mickey of Ulladulla’s Untitled (Fishing, Native Fauna and Flora) might be just coincidence, but “Jackson Pollock” with reference to Emily Kame Kngwarreye (Untitled, 1981 and 1995) probably is not. Throughout her life, Kngwarreye finished one painting per day on average; that’s less, and less thought through, than Jackson’s work. There’s also Pointillist tendencies with Poly Ngal. A collection of shields on a wall stands witness for different dialects of speaking in patterns and concentric circles in the many different regions of Australia. Some look decidedly African. With one of them free-standing in the room, you may admire the usability, the hilt on its backside. These objects once served a purpose, this was not l’art pour l’art! Or no, this is actually an artistic reproduction by Jarynanu David Downs, ca. 1983. Albert Namatjira's boomerang decorated with ‘Abos’ and ‘roos, and an ice cone in the centre (no, must be a tree) completes the bush fighter’s equipment. Having seen all this and more, you arrive at the last section, where they’ve put more conventional contemporary art, globalized, equalized, and, of course, politically correct. Here, Indigenous Australia proves, how today’s Aborigines basically do the same as everyone else. Even if it’s well-meant, it just looks familiar, seen too often before, everywhere. There’s (anti-)racism with a sculptured group of Australian KKK members, looking closer, it’s “HHH” written on their gowns, and no, I’ve no idea, why. They confront a dingo clan (of a different artist!) trapped in wire fences, cleaning themselves and sniffing each other like a good boy, and not eating babies (you remember Wa Lehulere's dogs at DB Kunsthalle?). Background information: Dingos have been treated poorly by White Australia, too. (Yet, they lost the Great Emu War, lest we forget. Let’s observe a minute of silence here.) All this looks like it could have been done anywhere in the modern world. Only by chance it’s Australia, or Aboriginal/Indigenous Australia, and it’s open-minded, antiracist, exchangeable in values no less than style. This is not the way to preserve diversity, I’m afraid. It’s the opposite: Equality. Take Austracism, 2003, a work by Vernon Ah Kee, the enlarged digital print of a text page: Afraid to express their opinions and be labelled a “racist”, people in anticipatory defence add the preamble “I’m not racist, but” - which will inevitably earn them that very label. Those few words relieve everyone from the annoying duty to listen, and potentially even debate, “unacceptable” views. Many of the ensuing phrases in Kee’s artwork seem perfectly normal, or perfectly debatable at least, expressing perceived/believed “facts” (that’s “opinions”) such as: “I’m not racist, but... ...if us white people can’t hunt native animals, then they shouldn’t be allowed to, either...” “..., but... ...my job is to guard against terrorism, and...” “..., but... ...they never even wore any clothes before we came”, “..., but... ...some of these Native Title claims are just unreasonable” (not knowing anything about “Native Titles”, the statement itself seems a legitimate opinion). Other statements might be idiotic, or, more civilized spoken: factually wrong, but where’s the problem with speech? “..., but... Aboriginal people weren’t doing anything with the land before we came, and...”, “..., but... ...I don’t know why Aboriginal people can’t look after their houses properly...” (i.e. different to how we do). No matter where you stand, no talk can never be the answer. The expression of differences does not equal racism, and, more controversially, it might be a bitter truth that differences can only ever exist by actively denouncing those who are different to one’s own difference (“they/the savages” eat with fingers/the left hand/chopsticks – without perceived superiority, your own manners will loose all claim to authority, which is not intrinsically bad - but element of a specific culture, a tiny piece of diversity, of human creation as opposed to utilitarian/mercantilist uniformity. Only “What we do is better than what they do” can ever create cultural pluralism). Isn’t it ironic: the more equality you seek, the more diversity you destroy, the more you create uniformity under one rule, the market. There’s no need to hold hands with everybody, equality does not mean diversity, it destroys it. And Tony, Ash, using readymade ashtrays with aboriginal motives to protest the use of historic and sacred imagery. He perceives it as disrespectful (... so what? just stop caring about everything, will you? He’s not happy with it, he's not obliged to buy, or pay attention. Simple as that, don’t get all worked up being “offended”. ... Sorry, seems I forgot: “I’m not racist, but...”). Getting (art) education and striving for “equality” sadly equals the triumph of the oppressor, the loss of your unique “yourness” that you so well preserved through oppression. Sorry for the outburst. What else? That’s not a whale, that’s a dugong - Alick Tipoti, Theo Tremblay, 2008. Then once again, you think to meet familiar names, Yhonnie Scarce under the influence of Damien Hirst, and Richard Bell channelling Roy Lichtenstein. Also neon triangles like countless Euro-Merican artists have done for decades, and photographs. One is briefly interesting, with a black man in an ancient naval uniform posing on the beach before a sailboat anchoring in the background. It’s not Oludah Equiano, but (probably) meant to satirize the discovery of the continent, that indeed not happened for the first time under Cap’n Cook’s command, but much earlier with the Aborigines’ ancestors, wherever those originated from. There’s even video art in another side room: Different faces, you’re all Australian, you’re all alike. It’s hard to judge, is this a contemporary art exhibition or a folkloristic one? And which would be the more interesting? Still worth a visit, let’s drink a Foster’s to that! Indigenous Australia, 17 November 2017-2 April 2018, me Collectors Room

World of Arts Magazine - Contemporary Art Criticism

Comments