Pablo’s back in Paris – The Reopened Picasso Museum

- (first published on artlifemagazine.com)

- Feb 9, 2015

- 6 min read

Updated: Mar 24, 2020

(Paris.) The renovation of Parisian Musée Picasso, established in 1985 and owning the world’s largest collection of the artist’s œuvre, started in 2009 and was initially scheduled for completion in spring 2012. With two and a half years delay, it finally reopened last October. During this time, many its treasures have toured the world, their lending fees contributing to pay the builders’ invoice (together with the insurance cheque for an eight million Euros worth sketchbook stolen right before the works started; a great loss, certainly, but also a somewhat happy coincidence).

If you’re interested in a new, in-depth, perspective on the Marais district, we advise you to visit on the first Sunday of any month, when all state owned museums are free of charge. The queue then starts one block away on a lovely square, where gentle guides orchestrate the masses in meandering movements away from the road and under the arcades of a nearby building, to the bewilderment of a “clochard” who’s made this place his living-room. At this point you still don’t know about the surprise that’s waiting for you at the other end of the line, behind the gate of the historic mansion that houses Musée Picasso. Arriving there, in about an hour from now, you will discover a second, equally long and even more artistically formed, queue inside the courtyard, and a placard declaring this the “Start of the Waiting Line”. If a metal plate could smile complacently, this one would.

What you’ve done so far was not waiting, but merely hanging out, or enjoying the surroundings. And indeed, there’s so much to discover! For example the art installations(?) in the adjoining residence’s garden: A wooden triangle in a sandbox that cannot possibly be a cellar entrance, a grid construction that, formed like an archway but open to the elements, cannot possibly serve any purpose and on which a retiree has just locked his bike despite all the bike stands in the front garden, the graffito of a boy with school cone in a street artistic protest against gentrification(?). Turning your eyes to the other side of the road, you read “trottoir chevalable”, literally “horse-able pavement”, a deep mystery as a) it would need to be a very small horse, and b) this signpost doesn’t look antique at all (it’s not even on Google Street View). That’s the great thing with art: it can explain all kinds of strange phenomena!

Perhaps it would be even more fun to observe all this in the sunshine, on a bright Parisian spring day, but it was your decision to come here on the 1st of February, when the sky’s dirty and the city of light looks nothing but grey. Grey, old stones, and the falling water’s ever unsure if to wear the fluffy white robe or go plain transparent. As mentioned above, the Picasso Museum is housed in one of those Parisian palaces that are usually lived in by oriental dictator’s families, fashion designers, football players or famous art collectors. One more placard introduces it by name: The Hotel Salé, the “Salted/Salty Residence” (“hotel” in French has a very extensive meaning). Most important is the accent on the “é”, as “Hotel Sale” would mean “Dirty Hotel”, and this is far from it. Even in a non-literal sense. Once inside, you will recognize the salt and pepper pattern in the staircase, where the monochrome marble floor meets with white walls and black steel railing.

Right now, still standing on the out-, and freezing on the inside, you feel like addressing the two Europeanized sphinxes on its roof: “Aren’t these people cold, is it only me? No? Then why won’t they go home?” And is that woman in her repulsive fur coat over there really wearing sunglasses? If you’d went to tell her, “these don’t make you look cool, only stupid”, you’d lose our place in the queue, so instead you start humming, “I were my sunglasses at night...” (Tiga&Zyntherius version, 2001). You feel regrets not to have shared a bottle with that friendly “clochard”, you’d be the better now, or warmer at least.

To keep the outspokenly non-cubist geometry of French design, this second queue is divided into two parts, with the centre of the courtyard a no-go area (we’ve recently learned these exist in Paris, have we not?). When you arrive at the next gate – this one is truly and really the entrance to the museum – you’ll discover that extended families with one tiny, sleeping, child are allowed to cut the line(s) and enter directly. The warden smiles at you, obviously taking your comprehension for granted, but you won’t even fake it. Instead, you come up with a business idea named “rent-a-brat”. Take twenty Euros and pay a candy. Should work. But just before retiring to a café and type the business plan, you, too, are allowed in.

Alright, so this is the temple dedicated to 20th Century’s (make that “one of history’s”) greatest artist, the museum, Barcelona would love to have. The antechamber welcomes us with early works, The Death of Casagemas, The Head Cutter (both from 1901), this latter title seemingly announces the first mental sprite of cubism in plain blue period. What need to talk about the art, painting’s Cassius Clay did not waste any time to find a style, genius is the antithesis to work.

It follows auto portraits from 1901 to 1972 in all different styles and grades of abstraction, then studies for the Demoiselles d’Avignon, first examples of cubist autopsy, and finally the full dose: a room with Sacre Coeur (1909/10), Man With a Guitar (1911-1913) and ... a Mandoline, also the magnificent assemblage Violin (1913). Visitors had to be prepared for this, and gently led to understanding.

The Picasso Museum neither sticks to a chronological nor a purely topological presentation, they found a great mix of both. The styles succeed each other, as an artist it must feel strange to succeed in everything with the only yet ever present danger to get bored all too easily. In the staircase, we’re reminded that in 1920, Picasso offhandedly invented Botero with Three Women at the Fountain. Upstairs, The huge Orator of 1932 meets The Bull that “sculpture” made from a bicycle’s saddle and handlebar that’s used for the reopening ads all over the city. There’s also an army of minotaurs with no thread to find out, and Picasso at the Corrida (I’d love to visit one once, as a supporter of the losing team, the bulls. Not much reason to cheer indeed, and even dangerous to do when we win, a familiar feeling to anyone whose regular team is chronically fighting relegation).

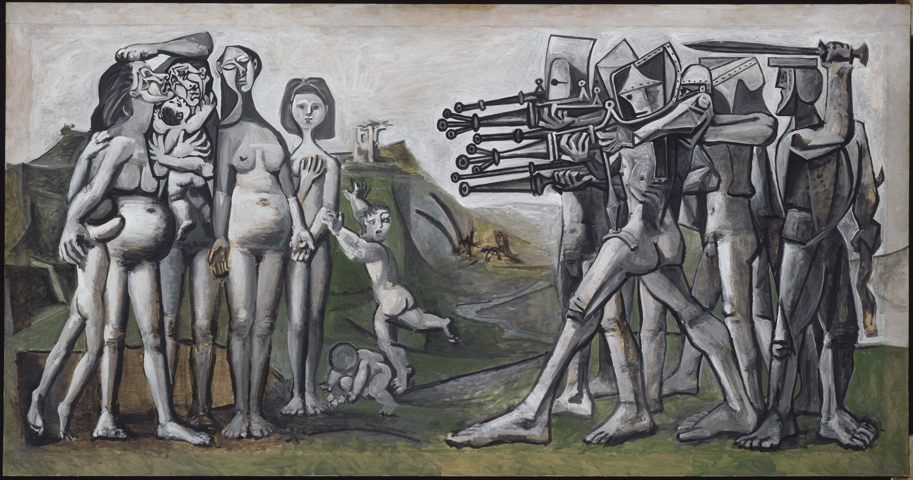

Another floor, a commemoration plaque of Picasso’s photographer Lucien Clergue who died in 2014. Later on, we find Picasso’s studio photographed not by him but by Brassai. A chamber of violence from a Cat Catching a Bird (1939) to a Massacre in Korea (1951), but no titledropping can ever be exhaustive, there are just too many masterpieces. Still further up, under the roof, we find pieces from the artist’s own art collection: Cezanne, van Dongen, Derain, Gauguin, Degas, Ernst, Douanier Rousseau, Modigliani, Miro, Matisse, Renoir, it’s a museum in its own right, and the master’s loyal sidekick Braque is here too. And there’s the tribal art, that influenced Picasso so much, that provided him with the means to express the novelty that was a fusion of ideas. Further above, only the sky (“sous le ciel, l’art”?).

To say, it’s a great collection would be shamefully understated.

The renovation of the old mansion has cost no more than the average Picasso painting, i.e. some thirty million Euros. It’s all relative, in the museum shop you can spend fifteen thousand Euros on a limited edition catalogue in ten tomes.

On the downside, we’re inclined to ask why they not just sold the Hotel Salé, and furbished a large container, or moved to the projects in the banlieue. I can’t exactly recall how the museum looked six years ago, but if there were still any traces left of the mansion’s past, they have been eliminated for good. Picasso who once declared “I want (to have/live in) an old house” (“Je veux une vieille maison”) would most certainly not feel at home here. Apart from the staircases, the interior looks exactly like any commercial gallery between LA and Beijing, a face- and characterless white cube, incapable to either offend or appeal to anyone. The white walls of Sainte Anne, the Parisian mental asylum, with an impotent sterility so completely out of character for lusty Pablito el Minotaur. If the master’s spirit manifests here, it will not leave the only, minuscule, room with wooden panelled walls like an ambassador’s residence, exhibiting a single bronze and a painting (you felt him there, genially laughing, godlikely creating or grabbing your girl?). This tiny cell is the salty and dirty residence that suits Picasso so much more than that depressing irrelevance of a pseudo-virginal white void. If a museum tries to copy Gagosian, it’s bound to lose. Everyone’s talking about marketing today, but then where’s your unique selling point?

The art itself, you say? We should just focus on the canvas, the bronze and ceramics, and admire Picasso’s perfection? Ok, good point. Yet, it’s hard to blend out the surroundings, when they’re are blinding our eyes, and what about set and setting? If you can dispose over a building as characterful and full of illustrious history as the Hotel Salé, why don’t you use it?

We’re only reassured, that nobody has turned the Louvre into an architectural copy of Perrotin Gallery yet. Enough, come and see for yourself (but please not all at the same time).

P.S.: This is the last time, we’ve complained about the queues at Parisian museums, promised!

Comments