No MA('a)M! - Keith Haring's Political Line at MAM, Paris

- (first published on artlifemagazine.com)

- Apr 25, 2013

- 6 min read

Updated: Mar 25, 2020

(Paris.) Ever since the stunning success of its Basquiat show back in 2011, the MAM (short for MAMVP, the Municipal Modern Art Museum of Paris) brooded over the question which artist could create similar waiting lines. Two years ago those were leading down all Wilson Avenue from Trocadero square to Pont de l'Alma, where it merged with the daily crowd of British tourists laying down their bouquets for a crashed princess by the torch sculpture mistaken for a rose (and, btw, it was the other side of the tunnel). Finally, somebody at MAM came up with the name Keith Haring, holding on closely to the Basquiat formula. But - hélas! - never trust the public, ever ungracious and capricious. Where the plan still seemed to work out on the opening night, by the next morning the rush had ebbed away, and now you may come to visit whenever you like without reserving a whole day for Godot. Thinking back two years again, Basquiat had the undeniable advantage of a simultaneous Larry Clark show, and what better excuse to go there than "I only came here for Basquiat"...?

Haring now.

The exhibition is called The Political Line, and to demonstrate how politics exceed the dead museum space, two Haringesqe graffiti got sprayed onto the street in front of the main entrance. Keith Haring's worldview is not hard to understand. He showed and tried to explain a violent world. He wanted to unveil the bloody truth behind human society, and maybe in the nineteen eighties this did not yet sound as naive as today.

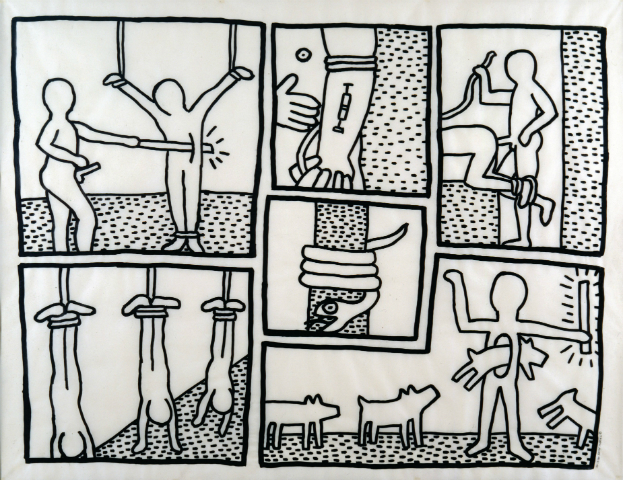

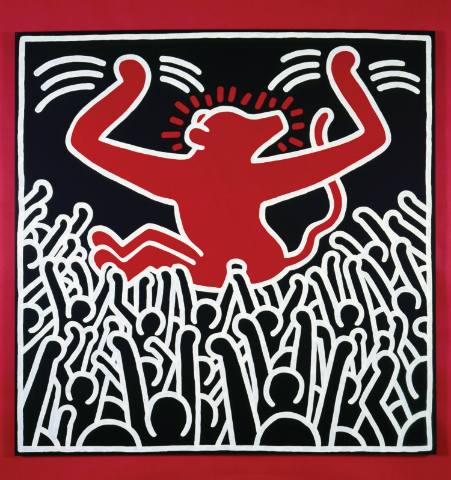

In his works we find either the manipulated masses hailing an evil leader, or the individual tortured by the many. All against one and one against all. For this, Keith Haring used a repertoire of ever returning forms. Egyptian and American Indian influenced stick men are battered and torn apart for spraying graffiti, having gay sex, or just for fun. Dogs are common, and Keith Haring's relation to them was not of the Ameropean affective kind. With him, we find the "miso-cynic" ("anti-canine"?) oriental attitude instead, Haring's dogmen are the leaders of the pack or the masses jumping through a victim's belly. In Egyptian mythology, the dog-headed god Anubis is the son of Seth, who for his part murdered his brother Osiris (an equivalent to the Cain and Abel story; btw: has anybody ever wondered how exactly the Neanderthalian got extinct after homo sapiens sapiens came into the world?). Anubis is identified with death, the other world, but he is an ambiguous figure like much of the Pyramids' pantheon.

The oppressors are further marked by dollar signs, the American flag or religious symbols; Mickey Mouse, the smurfs, television, electricity and Warhol all belong to the dark side of the force (Haring was a personal friend of Andy's, though). Some images from 1981 appear prophetical in retrospective: here the victims are marked by "+" symbols, some three years before "positive" became a (and about a decade later Haring's own) death sentence.

Keith Haring created a world of men, his figures cannot even be described as unisexual. Even the occasional scenes of birth leave it unclear, whether this is really a woman at work or a man giving birth by the backdoor. One thought might spring to mind when regarding the documentary photos of the artist at work. The gay community is said to be particularly keen on physical appearance and to put it mildly: Keith Haring did not look like Tom Cruise (or any other 200% heterosexual movie star, for that matter). This is indeed relevant to a discussion of his works as it might hint to his motivation to become an artist in the first place. Somehow phenomenological, Haring started with himself and expanded his personal experience to a broader worldview.

Everybody knows where meat comes from. It comes from the store (1978). Red lines stream down like blood from the words; the bad joke still has the potential to shock. Keith Haring was not a vegan, nor much interested in animal rights, but he surely liked ambivalence and self-contradiction. Whilst his works appear full of anti-capitalist rhetoric, he used uniquely designed pop up stores to sell T-Shirts and posters and worked for different companies.

A giant pig-monster's tongue turns into a green river covered with dollar signs, cars, electricity; human masses emerge to suck on the monster's teats. The masses are at the same time nourished and devoured by the system. For Haring, the alliance of money, power and religion was a historic reality; a continuous (political) line leads from an Egyptian sarcophagus over Michelangelo's David bust to the nineteen eighties. Dollar-, but also envy-, green, are David's locks in his copy of the Renaissance statue. It is covered with the suffering masses, so is the pharaonic coffin, so are amphorae and folding screens. The historic argument reappears in Haring's visual vocabulary from pyramids to UFOs. The belief in external powers is a means of oppression, but are "they" really responsible for what happens on earth - or might the bad things come from the inside? In Haring's universe, there is no simplistic "us" and "them", there is but human nature. In the end the dog (occasionally a monkey) stands for internal, natural powers, for the animal within.

Haring's statements are questions, even in his fight for gay rights he maintained a critical distance. He was well aware of the links between sex and violence, the leaders regularly appear with immense phalli and a gay daisy chain becomes just another mass. After all, this is what most human action comes down to. And those were the eighties; coming aware of its limits, the anything goes dreams from twenty years before dissolved into doubt and frustration. Haring's copulating men remind of Frank Zappa's nonchalant mixture of libertinism and hilarious sarcasm (Bobby Brown goes down, 1979).

The Yankee Dollar eats people and sends tanks to the world, some of Keith Haring's works could well put him on a no flight list today - no: he was not a patriot. Though when he attacks America, it only serves as a contemporary example for a historical constant. In his work, the exercise of power is ever indistinguishable from the abuse of power.

Keith Haring never offers an alternative, he was too smart to believe in classless utopias. He described the world as it is, taking back the one decisive step behind Marxism and other dreams of deliverance to gain timeless relevance. Beneath the neon colors, the flashy celebration, lies a deep pessimism. Keith Haring's paintings appear as accepting the will to power whilst denouncing it - and how could it be possible to change humanity without changing mankind?

Interesting in this context is the use of religious symbols. Haring's relation to religion is ambiguous: in his rejection of Christianity, he cannot disperse of its iconography, a tabula rasa of the human mind is not possible. Haring shows hell in Bosch tradition, only the cross is recognized as part of the evil and not a solution. Sin is a concept created by religion: in one untitled painting from 1985, snakes creep out - are created by - a bible. Sin comes into the world through religion, but is it really that simple? Probably not, and Haring knew it. The cross is just another club in the hands of the powers, an instrument, not a cause.

A surprise waits in the last room. The visitor may be tired when arriving here - it is a huge exhibition - but marked by terminal illness, Keith Haring tried to explore what he could have done with more time left. Only that with more time he probably never had tried anything similar.

In these works he gets more serious, death is no longer the comic strip trifle, but a real mystery. Violently cut off blossoms lie next to their vase in a still life that in its color fields (remotely) reminds of Matisse. An Unfinished Painting leaves three quarters of the canvas blank, and the color pours down like a stream of purple blood - a return to aforementioned supermarket meat. Only now it is the artist himself, and his blood murderous.

The show continues at Le 104, a huge cultural center/artist residence in the north of Paris. Here we find three sculptures and the series The Ten Commandments, continuing in the antichristian direction but not adding anything essentially new. Talking in snakes, not in tongues.

Keith Haring, The Political Line, MAM Paris, 19 April-18 August 2013

Comments