Mr Ed Has Something More to Say: Edward Hopper at Grand Palais, Paris

- (first published on artlifemagazine.com)

- Nov 6, 2012

- 7 min read

Updated: Mar 25, 2020

Paris - I did not know Hopper.

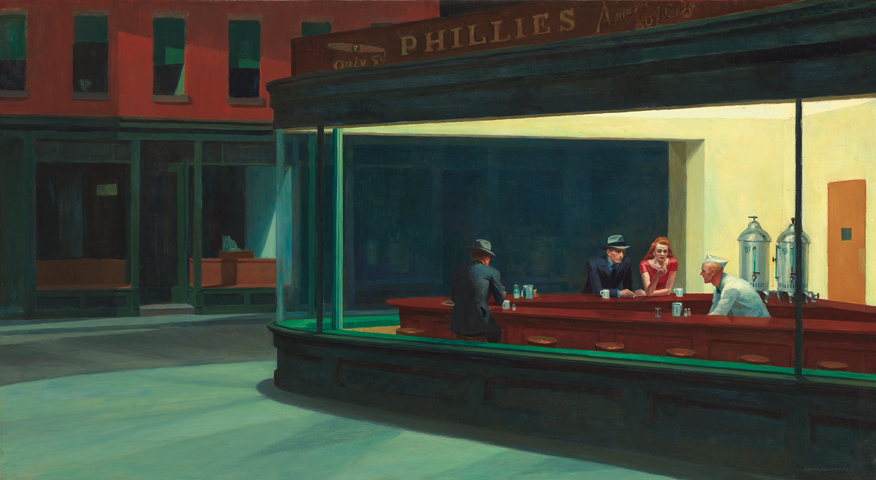

I mean, of course I knew "Nighthawks", but I thought that's all. And even in my perception of this painting I have been misled, as I never bothered to regard it attentively. Hopper, the painter of bar melancholy, of people having nothing to tell but their story to a glass.

I was wrong. This exhibition in presents Edward Hopper, who he really was and what his work is about. And be assured, it has little to do with shabby bars hanging a "Nighthawks" reproduction next to those Pool playing dogs.

But let's start from the beginning.

Grand Palais welcomes us with Paul Strand and Charles Sheeler's short film "Manhatta" (1921). Inspired by Walt Whitman's poem of the same title, it shows a hustling and bustling New York City - images highly opposed to the paintings that will follow. We meet Hopper's (supposed) influences, Robert Henri who was his teacher at New York School of Art, George Bellows, Walter Sickert, Félix Vallotton; Grand Palais also borrowed two Degas and a Pissarro for this exhibition. A nice introduction, context and background are set for the following tour of Edward Hopper's career.

While earning his life with illustrations in Art Deco style, Hopper found his sujet as early as on the occasion of three trips to Paris in 20th century's first decade, when he produced numerous studies of people and places. From 1914 onwards, it is hard to recognise any evolution in his work, to date a Hopper oil painting must be a tough job for the keenest expert as he always stayed true to his style.

For every artwork there are two questions to discuss - what is depicted and how. The latter is easily answered here, Hopper focused on space(s) and light effects; his trait is exact, minimalist and realistic at once, in a sense close to photography. Every inch of the canvas is covered with colour, and still there is emptiness. Hopper's scenes are void, they show depopulated streets and rooms too large for the few personages scattered within. These are not the outcomes of some apocalyptic event, but something connected to the state of things itself. If there is melancholy in Hopper's pictures, it derives from this emptiness.

Closely connected is the lack of motion and tension, his paintings are "still lives" not in art historical but in literal sense. In all the works of this exhibition, only one character seems in a hurry, a nun pushing a baby buggy all alone on the sidewalk (anxious not to be seen? "New York Pavements", 1924-25). For the others, the store advertising 'Prescription Drugs' ("Drug Store", 1927) sells only tranquilisers and no stimulants.

Hopper did not care in the slightest about the moving masses, about the energy contemporary photographers captured in New York's popular quarters. He has often been referred to as an American painter, and he most truly was. His works show almost exclusively New York and the East Coast, but in a tranquil version, stripped of all dynamics. And his chosen few represent a class, he portrayed the upper class he was born into himself, or to use a more suitable term: the establishment.

In fact this seems to be Edward Hopper's true concern: the existence of an American establishment, the settlement of a dream that had been identified with never-ending agility and change. The west has been conquered, the country's expansion and growth come to a halt. The wave of pioneers has ebbed off long ago, and boredom sets in to business as usual.

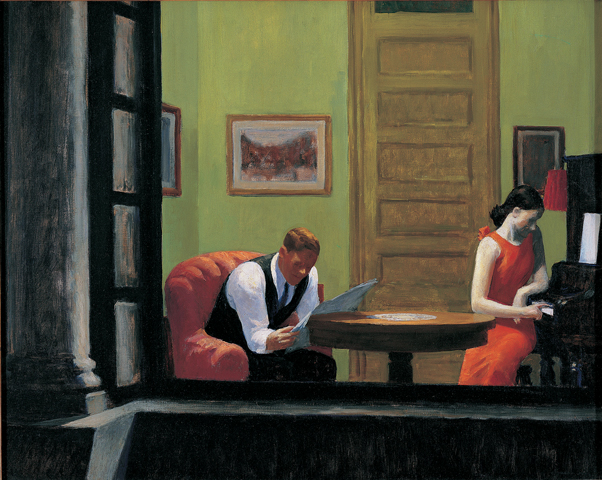

Hopper's characters have installed themselves in comfortable homes, and if the city still offers unlimited possibilities - who cares? They have found their role, everything is natural, normal, settled. These are no losers, this not the other side of the medal, the nameless masses, if Hopper attacked the American dream he did it in a less obvious but all the more devastating way: in defying the dream's value itself, its sense and power to satisfy any longing. A naked woman sits in her apartment at "11 AM" (1926), in what appears not to be just a moment of silence, but the daily routine of finding one reason to dress. Hopper's concern is not to show those in the shadows, but those in the light, and how this light not only illuminates but creates nothingness. People who don't suffer from any want but the lack of novelty, of challenge and adventure. Sometimes they live beyond talking, the couple in a "Room in New York" (1932) has nothing left to say, he stares at a paper, while she stands at the piano, gliding her fingers over the keys. These are interiors of people who own pianos. Of people who dress "European". Who at times are only present via their dependants, a cleaning lady like a piece of furniture (who still did not speak a word in Spanish) in another "Apartment House" (1923).

The society is born, now it comes to age. "First Row Orchestra" (1951) shows even the first one and a half rows of an auditorium, men and women in tailcoat and fur, and absence again, as half of the seats are yet to be taken. The emptiness returns in every work.

It is Hopper's parallel execution of landscapes that brings me to conclude, part of it is not simple solitude but a metaphor for the country. A country that is immense but holds no white spots any longer. The emptiness in these pictures is both the emptiness of success and the emptiness of a continent that once seemed endless. There is a nostalgia for the times when a new world was waiting to be discovered and Edward Hopper kept searching for that unspoilt openness, but at every place of natural beauty like "The Camel's Hump" (1931) we discover a road in the background.

Buildings on the countryside appear as if standing their place for a immeasurable long time, deeply rooted in the surrounding nature, "Lighthouse Hill" (1927), "Hotel by a Railroad" (1952), or the spooky "House by the Railroad" (1925), this one clearly a major influence for the architecture of Bates' Motel in "Psycho".

In "Two on the Aisle" (1927) the theatre is empty except of a couple taking their seats and a lone reader who like them arrived two hours early for the play. The omnipresent cultural status symbols - books, pianos, theatres and opera houses - in Hopper's work point not only to conservative stagnancy, but are apparently not taken serious by his personages. Never we see people following a piece in sincere affection, they just wait to see and be seen; and when they read it is either to avoid conversation or the book is held at an impossible angle ("Hotel Room" 1931) - their thoughts are wandering, they do not really take in a single word.

When not waiting for a spectacle to begin, they sail ("Ground Swell", 1939) and ride ("Bridle Path", 1939); and emptiness not accompanies, but takes them everywhere. There is a type of melancholy that sets in with the abundance of time and the lack of challenge, of adventure that have been traded in for security and comforts of an established culture.

When at work, the same lassitude can be observed, "The office at night" (1940) is a scene of routine: while a secretary searches a file from a drawer, her boss reads a letter, but his desk is not spilling over with work. This is no lively exception, no extraordinary event, it is simply as they do.

There is still so much life left after the beauty has gone. And once you have tried everything from golf to alcoholism, why not give philosophy a try? In "Excursion into Philosophy" (1959), a book laid aside leaves the reader clueless. He studies the rectangle of light falling to his feet by a large window in the back, and the blue sky outside looks inviting as do the bare buttocks of the woman on the bed behind him. She curls away, her head facing the wall. Distractions may vary, none will fill the gap.

And here we go: "Nighthawks" (1942). Part of a troika formed with the "Mona Lisa" and Monet's Water Lilies of the paintings the most reproduced on posters, postcards, coffee mugs and jigsaw puzzles. By taking a closer look it seems that again the popular reception is not quite right. This is not simply about big city blues. This is no lost generation "sharing a drink called loneliness" (Billy Joel, "Piano Man"). Just look at them. The couple is actually agitated, they are talking to the attentive barman, perfectly well-dressed and pleasantly smelling they might be returning from a party at Gatsby's to get that last shot to load on all the blame the next morning. And the creepy guy (?) we see from behind, who might or might not be a self-portrait of Edward Hopper, is listening to them and not to his whiskey, ready to throw in a witty remark. Everything is clean, everything is in order, the bright neon lights shine for them. They are not sad, for one night they forgot the emptiness - only we see how their escape is futile. Hopper shows them surrounded by space and they will have to surrender soon. The painting is not a scene of defeat but of menace and momentary shelter.

"Intermission" (1963) once more features a woman waiting in the front row of a theatre, waiting for something to come, unable to create that something herself. Just like the group of sunbathers in "People in the Sun" three years earlier (yes, that's 1963) - it made me think of Thomas Mann's "Magic Mountain" (1924) but contrary to that work of world literature there will come no war to deliver them from paradisiac boredom.

In 1966, "Two Comedians" on stage bow to the audience.

The show is over.

Edward Hopper, Grand Palais, Paris, 10 October 2012 through 28 January 2013

Comments