Marcel Readily Made Paintings, Even. Marcel Duchamp at Centre Pompidou

- (first published on artlifemagazine.com)

- Nov 3, 2014

- 6 min read

Updated: Mar 24, 2020

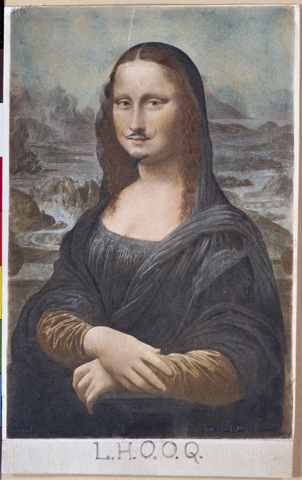

(Paris.) L.H.O.O.Q. Not to confuse with L.V.M.H., the name of Bernard Arnault’s little shop of luxury, that is indirectly honoured on Centre Pompidou’s first floor, where a Frank Gehry show celebrates the arrival of a new competitor on the Parisian museum scene (“I scratch your back and you scratch mine”, more on this soon). This is interesting, too, if you like architecture models, although it provides no answer to the question, when the architect dropped the “O.” from his brand name, or why the Pompidou has not yet replaced the “R” that has fallen from the wall leaving only “F ANK GEHRY”. But we are digressing, this should really be about L.H.O.O.Q. Pronounced in French “el(le)-a ch-au(d)-au-cu(l)”, the acronym literally translates to “her arse is hot”, meaning not “She’s a H.O.P.A.”, but “She’s randy”. L.H.O.O.Q. are the letters Marcel Duchamp wrote on a postcard of the Mona Lisa in 1919, beside drawing her a mustachio. It is one of his legendary works, and it is one of the first we see at Centre Pompidou’s Duchamp retrospective.

Today, Marcel Duchamp is considered one of, if not 20th Century’s most influential artist. He also incarnates everything that the uninitiated hate about contemporary art. Picasso, Matisse were no less revolutionary and important for art history, yet they still made pretty pictures. Marcel Duchamp on the other side is identified with intellectual plays; he’s the godfather of conceptual art who dared doing “what everybody could”. In other words, he revolutionised the concept and definition of art itself, and after a hundred years still poses a provocation to Sunday museum goers.

One would expect this is not a show for tourists, nothing you would visit with your wife and kids on a Europe-in-four-days trip, chasing photos for your friends back home in Shenzhen, Calcutta or Chicago, and accordingly the visitor information sheets are much more taken in French than in English. This is a mistake: the Pompidou show highlights not Duchamp’s work as the declared “destroyer of Painting”, but his being a painter himself, and he was an eminent one before turning his back on what he would then call “retinal art” in around 1914. Baptized in true Duchampian diction Marcel Duchamp: La peinture, même (Marcel Duchamp: Painting, Even/Actually/Itself), the show tries to make us understand him as far as possible. Marcel Duchamp is put in context of time and knowledge; books and other artists’ paintings are everywhere in an attempt to capture his inspirations, his intellectual curriculum.

The first room, the exhibition’s antechamber, proves significant for the concept. There is the Boite-en-valise (The Box in a Valise, 1936-41), in which he included miniature replicas of many his earlier pieces, but there are also – and predominantly - drawings. We find the same Cranach painting recreated in a photo by Man Ray starring Duchamp as his model, and Duchamp’s own copy in a drawing, as well as more papers from the series Selected Details from... (...Ingrès, ... Courbet, ... Redeon) that, created shortly before the artist’s death in 1968, look surprisingly non-Duchampian (of course, the experts care more about their eroticism and explanatory potential for other works).

Later, it’s all about recreating an era. Braque, Brancusi, Kupka, De Chirico, Picabia, Redeon, Kandinsky, the list is all but exhaustive. This is not a Marcel Duchamp exhibition, it’s a course in art history (and a great opportunity for Centre Pompidou to show more of its impressive collection). It seems there are at least as many works from other artists as from Marcel Duchamp himself, and the exhibition is well worth a visit for them alone. Only Manet’s Olimpia and Dejeuner sur l’herbe seem too important to attend in person, and appear in Jacques Villons’s remakes instead.

Duchamp’s art just plays a part, nonchalantly mingled in. For example the futurist/cubist Nu descendant un escalier No 1 and No 2 (Nude Descending a Stairs, 1912), later copied in Fernand Leger’s L’escalier from 1914. Or Le Baptème (The Baptism) contributing to the bathers trend of those years. How closely all these artists influenced each other, how they changed styles and movements, and how Duchamp some time or another worked in the style of everyone else was never so evident as here where said Baptème (1911) hangs next to André Derain’s Baigneuses (1908), and a Kandinsky landscape (Landschaft mit Turm, 1908) next to one of Duchamp’s (Paysage, 1911).

For many of Duchamp’s paintings there are preparatory studies to illustrate how he arrived at the final version. In a larger sense, his Chess Game (1910) and Chess Player (1911) can be considered studies for the artist’s life itself, as Duchamp was to quit art and focus on playing chess after 1923 (a courageous decision for anybody French, as in French the game is called “echec”, a term otherwise meaning “failure”. Hobby-etymologists like us dream of medieval crusaders forfeiting horse and castle to smart Arabs in a board game before ever reaching the “Holy Land”. “Excusez mon echec, milord.” Probably completely inaccurate.).

It’s not all about painting, though. The Pompidou has reserved a corner for Marcel Duchamp’s short films of carousel lights in the night and kaleidoscopes on naked bodies; later Op Art hardly ever went beyond that. And of course there’s the Bicycle Wheel (1913) that even before L.H.O.O.Q. marked the invention of the Readymade: industrial products transformed into “art” by nothing more than their placing in an artistic context, an exhibition, a museum. It is joined by the Bottle Rack (1914) and the Hat Rack (1917), the latter’s shadows on the floor again referring to optical illusions. One might regret the absence of the infamous urinal turned artwork by its hanging upside down and adding the signature “R Mutt” (we won’t bore you with the significations and allusions of Duchamp’s nomenclature here). It is only present in a photograph, perhaps to prevent new attacks, as the work (i.e. one of its reproductions, as there exists no original) has been made the receiving end of an aggressive performance twice before in France.

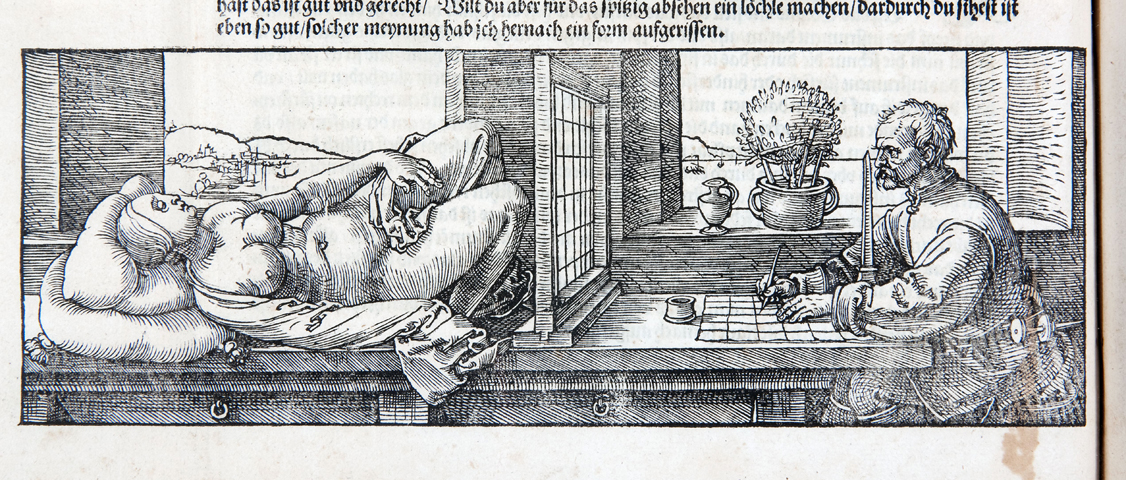

Étant donnés: 1° la chute d'eau / 2° le gaz d'éclairage (Given: 1 The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas), the installation Marcel Duchamp worked on secretly for twenty years (1946-66) loses much of its interest in a 1:10 model. A pity it cannot recreate the experience of the original that reduces the beholder to a Peeping Tom, forced to gaze through a hole in the door on that fantastical landscape and distorted female body, faceless, victimised, yet holding a light, naked yet missing the genitals. This reproduction is more of a documentation explaining how the work “works” than the real deal. Duchamp who throughout his life frequently changed residence between France and the US sold the original to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where it was to be unveiled only after his death. The installation owes some influence to Albrecht Dürer’s Underweysung der Messung (1525), but more than art, it talks about death and desire, nature and nurture/culture, it includes and shuts the viewer out of paradise and hell at the same time. The artist’s female persona “rRose Selavie (“Eros, c’est la vie” - “Eros, that’s life”) replaced by “rRose Selamort” (“Eros That’s Death”), or a depiction of the human subconscious? Duchamp left no hint to interpretation. Which is not the case for another emblematic work of his: La mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même [Le Grand Verre] (The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even [The Large Glass], 1915-23). Throughout the exhibition vitrines with notes by the artist’s hand bear witness of its exhaustive theoretic content and prepare for the work itself. It’s also a reproduction, but in the actual size of 277.5 cm x 175.9 cm (109.25 in x 69.25 in), more impressive – and more reminiscent of a guillotine - than any photograph would suggest. Centre Pompidou surrounded it with even more texts, just as willed by Duchamp, and as his handwriting is challenging to say the least, they thankfully added an audio track. Still, there is not the valid interpretation. Geometry is important - fascinated by Mathematics, Duchamp tried to represent the “Fourth Dimension” in other works before -, and the internal barrier appears similar to the later one separating viewer and work (male and female, art and life) in Given...; the two parts hermetically sealed the one from the other. Duchamp used his own personal iconography that is impossible to decipher in every detail. Some scholars think today, the whole work were but a joke on art critique, and no definite meaning ever intended, which could turn it a metaphor for life, couldn’t it?

The last work here is L’envers de la peinture (The Opposite/Backside of Painting, 1955): again the Mona Lisa, moustached again, but cooled down by now.

Once you’re at Centre Pompidou you might also visit the exhibition of Latifa Echakch, last year’s winner of the Marcel Duchamp Prize, which is awarded at the fiac art fair. She presents an installation, that could be described as the backside of clouds, or dreams. But there’s no direct rapport between the prize and Duchamp’s work other than the awardee necessarily being French or living in France.

Marcel Duchamp: La peinture, même, Centre Pompidou, 24 September-5 January 2014

Comments