Loris Greaud, Pompidou and Louvre, Looks like he made it

- (first published on artlifemagazine.com)

- Jun 26, 2013

- 4 min read

Updated: Mar 25, 2020

(Paris.) Question: When you are a 34-year-old French artist, what would be the best thing that could happen to you?

Answer: To be booked for a double show at Centre Pompidou and the Louvre.

The dream just came true for Loris Gréaud. From this day on, he has to be counted among the most established French artists. Certainly not a poor man before (represented by Yvon Lambert in Paris and Pace in Beijing, New York and London), now he made it to pure glory.

It needs to be said though, that this double show at two of the world's most prestigious art institutions may sound a bit more spectacular than it actually is. There is only one (big) work each, and they are installed in the entrance halls, not in the regular exhibition spaces. On the other hand, this seems rather reassuring: Loris Gréaud doesn't need to retire right now, there are still goals to reach.

At both venues, the show is called [I]. Pompidou's press release explains this as referring to the English word "I" and some "imaginary unit" in mathematics (I did not exactly get this part). Maybe the artist also got inspired by that band's name: Δ (Alt-J).

At Centre Pompidou, a spiral staircase rotates around its own axis inside of a solid support structure, all painted deep black. A platform on top serves at the departure point for a man jumping down into an air cushion ten meters below. His somersault should deserve a B-score of 8.0, with only a slight deduction for not standing the landing. Spectators might be a bit disappointed when learning afterwards, the athlete is not Loris Gréaud himself, but a trained gymnast, one of several who take turns over the day, perpetually walking upstairs and jumping down.

Chris Burden would have done it himself. Without the air cushion.

It cannot come as a surprise, that Centre Pompidou cordoned off the one side from which courageous(/stupid) visitors could try the jump themselves. Safety rules, art does no longer contest society but confirms the angst-ridden standstill. But okay, this is not called a performance, it is a sculpture in the traditional one-way sense, the audience is not meant to participate. And as a sculpture it performs well.

The form is supposed to remind us of different traditions in art, utopist towers (compare Vladimir Tatlin's never realized Tower for the Third International), falling bodies and moving machines. Sounds legit.

The DNA double helix would be another possible association. It circles around without advancing, while the human jumper surpasses the natural form on his stairway to heaven, only to fall back into the unknown. And when Centre Pompidou talks about mathematical and physical units, it should be allowed to think of energy forms, from potential to kinetic, too. Finally, the sculpture might be described as a man-machine, wherein man and motor jointly move.

Loris Gréaud definitely took inspiration from Yves Klein's Le saut dans le vide (Leap into the Void, 1968), a photomontage (for the young generation: that's what you called photoshopping before there was Photoshop) of the artist in free fall. Back then it was about the experience of immateriality and levitation. Here at Pompidou, the fall is not a frozen moment but an event that takes place - and time. The work advances to eternal recurrence instead of capturing/depicting an instant.

But whatever the interpretation, if you enjoy watching Acapulco Cliff Diving on TV, you will like this arty version (minus the muscular bodies, tight slips and beautiful coastline), too.

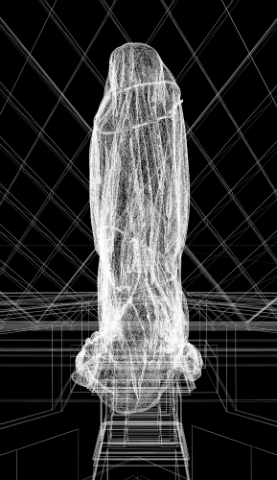

The Louvre keeps it more traditional. In the entrance hall (/dome) we see an all-new Christo and Jeanne-Claude (R.I.P.). Or almost, as Loris Gréaud created a wrapped statue, where the wrapping is of the same material as, and a part of, the statue.

The phallic form of the preliminary CAD sketches (see the example above) does not really show in the finished work, it rests unclear whether it was intended or not.

Officially, this part of [I] is supposed to recall Michelangelo's Revolting Slave, along with artworks awaiting restoration or unveiling. Maybe there is also some guerilla criticism of the museum's expansion to Abu Dhabi: This wrapping could well be a burka (or a monk's/nun's habit, for that matter).

Beside the wrappings, the figure is tied with ropes, just like a corpse the Mafia quickly needs to dispose of. But then again: it stands upright.

Faceless suffering as the human condition is a topic that goes well with all the Louvre's religious works.

Though a human form without a face is not a revolutionary idea, it nevertheless rests unsettling; we recognize the hidden body and instinctively search for the eyes. The sculpture captures some of the mystery (aura) of ancient art, shielded from our view and full understanding. Has it to be protected from us, or we from it, would the ancient cover their eyes in face of contemporary art?

At the Louvre, art history still regards us.

Loris Gréaud, [I], Centre Pompidou, 19 June-15 July 2013; The Louvre, 19 June 2013-20 January 2014

Comments