Meese, Richter, TAL R. Art in the Hinterlands

- Christian Hain

- May 28, 2018

- 7 min read

Updated: Mar 23, 2020

(Stade.) Espoo (FIN), Holstebro (DEN), Stade (GER) - which one doesn’t belong? No, wait, let me rephrase that: Espoo, Holstebro, Stade, contemporary art – which one doesn’t belong?

Daniel Richter, Jonathan Meese and TAL R are used to showing their art around the globe, from Berlin to Basel, New York to Shanghai, and when in Northern Germany, it should be Hamburg’s Kunsthalle, in Denmark the Louisiana, and in Finland – well, are there any art museums in Finland, actually? But now, the trio leaves on an expedition to the outback with the first halt being Stade, a small town fifty kilometres down the river Elbe from Hamburg. For Richter and Meese, it’s the second trip, having shown at the same venue, the municipal Kunsthaus (“House of Art”) fifteen(?) years ago already.

Stade is known for – no, scrap that, Stade is NOT known. It only ever gets mentioned in connection to its nuclear power plant which was one of the first, if not the first, built on German soil, and it has been out of service for years. An American chemical company also operates a plant here, further add a local community descending from fishermen and farmers (we’re on the doorstep of Europe’s largest apple growing area), and you don’t have to be particularly gifted to come up with the idea to some mutant horror B-movie in Wrong Turn tradition. Car registration plates for Stade by the way - that in Germany are tied to the owner’s place of residence – start with “STD”, a fact that regularly makes foreign visitors chuckle. You would not want any closer ties with the local populace.

Putting it politely, they are a down to earth people, with a rather hesitant attitude towards all things art - especially if it’s contemporary (which they take for a synonym of “nonsense”, or “fraud”). It’s a solemn, protestant, no fuss, folks living in the lowlands, dominated by Hamburg’s sober “Hanseatism”. The local press is well aware of this (politely spoken, again; more honestly: they don’t know better) when reporting among the lines of “think you could do it yourself”, ”children’s room aesthetics”, “pop art”, &ct. Kunsthaus tries the best to educate the masses, and bring art to the plains which is a honourable endeavour indeed: They offer guided tours and weekly lectures with titles such as “Self-Dramatisation as an Artistic Strategy”, “Nothing is Possible without Humour – Least of All When Things Get Serious”, “Feeling Lost in the Art of Meese, Richter, and TAL R?”, “Crossing Borders in Art – Past and Present”, “Are Humour and Irony Essential to Art?”.

They won’t bite, it’s all good, entertainment. Move along, nothing to see here...

And yet, there seems something amiss with Kunsthaus demanding an entry fee of eight Euros. That’s not so charitable anymore, not so much “educating the lower classes”, not so very provincial, but right up to Berlin standards. They sure have annoying insurance fees to pay and patrons get free admission to the local archaeological and folklore museums on top (you won’t claim it), but still... I enjoyed my hour-long visit undisturbed by other people. The show might appeal more to the tourist - there are those in Stade, and not only relatives of French engineers working at the nearby Airbus plant in Hamburg-Finkenwerder. Stade’s inner city is quite picturesque.

Today, it’s already newsworthy, in a bad way, when an institution shows three middle aged white males and nobody else – is this even legal anymore? It might only still pass in a sleepy provincial town like Stade (or Espoo, Finland, and Holstebro, Denmark), places far from the world’s metropoles, where life is still worth living but ultimately less fun.

Unfortunately, the show and the way it’s marketed feel surprisingly... conservative, stale and antiquated even. Forcedly provocative, with artists donning “crazy” costumes for the promo photos - when did you last see something like that (1916?). You get that eerie feeling of having travelled back in time a hundred years and more to an era when people were awed, and scandalized, by the first(?) waves of “crazy”, “unconventional” artists, a cliché we thought been done away with decades ago. Only on artists’ carnival parties you'd still expect to find the Dadaist, the Roaring Twenties Montmartrian, but certainly not out there in the wild, until you see photos of those three in fancy dress.

Has it been missed? Find the answer for yourself. Of course, it might all be part of the concept, a strategy to prove the unchanging attitudes of rural life: nothing’s happening here – or revealing of the artists’ very own stereotypes. More important, and disappointing: Much of the art doesn’t look any younger than the 1980s, either.

The title Bavid Dowie matches the first impression. David Bowie was the idol of a generation, a symbol of the 1980s, and most successful in an art and design context. No NYC Julian Schnabel opening without Bowie playing on the art collector’s walkman (art collectors whose role models were called Gordon Gecko, or Scarface). Today, nobody gives a – about Bowie who died some years ago. There’s this line from late Nineties German HipHop band Kirmes, citing their childhood hard rock idols and adding: “Erkennungssignale einer veralteten Jugend” - “Identifying Signals of an Outdated Youth”. When millionaire artists revisit their youth and childhood - Meese put some cuddly toys in the window sills, readymade or decoration -, is this a particularly expressive, or innovative, variant of the bourgeois midlife crisis?

The most obvious Bowie reference hides (more of less) in the show’s only video, The Man Who Fell on Earth; it shows the trio from the back and reading aloud the script of the eponymous movie starring, indeed: David Bowie. It’s projected upside down to a wall.

Spanning over three levels of a historic warehouse, and extending to a sailing trawler in the canal outside, Bavid Dowie is a rather large show. Not every frame hangs perfectly fixed on the wall, not every work is labelled – who, for example, is responsible for that nice Vanity sculpture, marble with basecap and a mirror? – but the little imperfections make it only the more likeable. Some works have been painted six-handedly, among them a portrait of the group’s spiritual leader Jonathan Meese. For Bavid Dowie, he adds tens and hundreds of automated drawings, lazy scribblings of repetitive schoolboy humour on the surface, and postcultural sampling of erstwhile meaningful iconography below. A naive and insolent student on a gallery excursion in Paris, I once asked Meese’s dealer about his stance in the controversy: Is Meese truly relevant or just a clown? D.T. frowned: “He's sold every work on the first day of Art Basel Miami”, cutting short any further discussion. Cannot argue with success, can you? (Now don’t tell me of flies and their preferences.)

Also some sculpture collages/installations in which, for example, the face of Edvard Munch’s Screamer (or Ghostface Killer from the Scream movie franchise), transplanted on the body of a mannequin, joins an abstract marble(?) something, a Sponge Bob balloon, and a Jeff Koons-y lobster eating hamburgers from a painter’s palette, “Nachwelt”/”Posterity” written on its claw - all these parts presented on a storeroom pallet (German uses the same word for “palette” and “pallet”). Ok, that’s pretty smart actually. What is art, who, and what, will survive – and whose judgement?

Another, much smaller, installation holds a swarm of moths prisoners in a plexiglass case, together with toy figurines and a sculpture, or maybe they’ve found the way in all on their own, but not out again. PETA did not intervene. Yet. There’s something to Meese’s sculptures that his paintings lack.

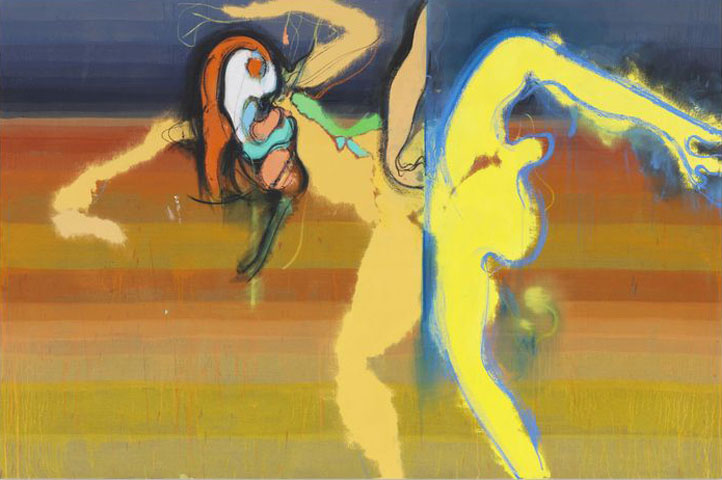

For large parts, Bavid Dowie feels like a Meese solo, but it would be hard for anyone to hold his own among the noise. Daniel Richter masters the situation a little better, mostly because he's the most skilled painter of the pack (by far, and you could add a lot more, and not only German, painters: Just look at the magnificent In the Meantime, 2015). He's built his career, his public persona, on a rebellious punk youth, making extensive use of the imagery in earlier paintings. In Stade, he shows strictly divided colour fields without even blurry frontiers and calls it Praise of Regionalism (or: ... Sectarianism). Not that I would mind, it’s always great to meet your own conservatism in the most unexpected of places, talking of true diversity instead of fashionable homogeneity, instead of pouring all colours into the same bucket that only ever creates a uniform brownish-grey nothingness. But most certainly he meant it ironic. And it's a Rorschach test, do you see two snails on a collision course, too?

TAL R all but vanishes in the group, smothered by the flashier egos, Meese’s voluntary trash, Richter’s imposing lines in large formats. R’s also added the fewest paintings, preferring to participate in the terzettos. It seems safe to assume, all three had fun in preparing the show, it certainly looks like it. They might have met for a night or two over an empty canvas and a (/some) bottle(/s) of Vodka. That’s how it’s supposed to look, anyway. In truth, there’s been much more work, and time, involved.

Our artists are not fundamentally opposed to innovation. Only weeks ago, Jonathan Meese presented a VR film at Martin Gropius Bau that focused on a spatial multiplication of his self and his omnipresent mother, painting and talking the time away. It felt reminiscent of the early days of film when the technique alone was still revolutionary enough to impress, and all the relevance lying in novelty and “progress”. Likewise, that Virtual Reality experience offered a glimpse into a future genre of art, a glimpse of things to come.

Would it have been asking too much to bring the same to Stade? Why choose the old, and lame, automatisms instead, why resort to the tried (too much) instruments of yesteryear in ridiculous and toothless “provocation”, only to satisfy the target group’s expectations, people who’ve heard it all before and who know exactly where to put it? It takes a special kind of arrogance to paint an artist how the average Stader imagines him. Why not challenge a supposedly backward public with the means of tomorrow – even here, far from the trodden paths of the artworld? You’d get more response, and your show would feel less like the discarded remains from the table of the hip - indeed: less provincial.

Bavid Dowie, 19 May-23 September 2018, Kunsthaus Stade

World of arts Magazine – Contemorary Art Criticism

Comments