Jean-Michel Othoniel and Johan Creten, from Delacroix to Perrotin

- (first published on artlifemagazine.com)

- Jan 26, 2013

- 5 min read

Updated: Mar 25, 2020

(Paris.) An art dealer has reached the top level when you start to wonder if he still adapts his schedule to museum shows or if it might actually be the other way round.

Emmanuel Perrotin has reached that stage.

Probably it was still the gallery who seized the opportunity and mounted a parallel exhibition of Wim Delvoye after the Louvre took the decision to present the artist last year. But when the rather unimportant Delacroix Museum now presents Des Fleurs en Hiver (Flowers in Winter) with Johan Creten and Jean-Michel Othoniel joining the local hero Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863), and simultaneously Creten and Othoniel are on show at Perrotin, the distribution of roles, the answer to the question who is in charge and who follows, might be different. Not to forget the close collaboration between Delacroix Museum and the Louvre, for the regular Louvre admission price you can as well buy a combi ticket for both institutions (valid the same day).

Networking, baby!

There is no need to complain as long as the outcome benefits everybody, museum, gallery, artists and public alike. In this case we have such a win-win(-win-win) situation: The Delacroix Museum reaches a significantly younger and broader public, the gallery gets free promotion, the public gets art and the artists another entry to their CV.

Let's start with Perrotin's part. The famous gallery resides in a magnificent manor and an adjoining garage in the Marais district. Perrotin proves all those wrong who still hold on to the belief, a gallery needed a distinct style of its own. Important galleries offer a bit of everything and do not specialise in any style; by attracting collectors of all kinds they are less dependant on trends. Perrotin usually exhibits three artists at a time, so no matter when you visit you should find something at your taste. Less friendly said, the motto of these shows could too often be "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly".

The Belgian artist Johan Creten proves ceramics is not a dead genre. His exhibition is named The Vivisector, after a book by Patrick White that Creten says to have influenced his decision to become an artist many years ago. The title is mirrored by the exhibition's scenography. In the first room four giant owls are holding a meeting that we feel to disturb with our presence. Although their faces look very human, there is no difficulty in identifying them as what they are. Two more birds in the following room appear less conventionally sculpted; approaching the abstract they are not perfectly finished but in parts only suggested. Human bodies then come into play, a man and a woman each surrounded by unidentifiable yet strangely familiar forms. Finally we see these forms alone and the best term to describe them might be 'biological'. Confronted with these Reliefs as is their title, you will think of an ear or a rose, oysters, an octopus or -sy. Human, animalistic and vegetal, male and female forms get merged into one object.

The exhibition closes with even more reduced, even more open forms, that might be stylised owls again, or broken shells?

Johan Creten does a vivisection of life itself without causing any harm. He distils life's basic forms into artworks that are not exactly beautiful but fascinating.

On the gallery's first floor Jean-Michel Othoniel shows two works, each repeated in several variations.

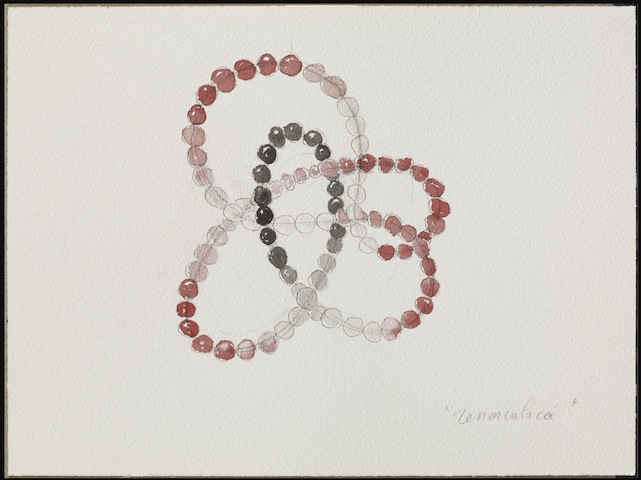

For once there are his well-known giant pearl necklaces from glass and stainless steal. Wound in irregular shapes, they are suspended in the air or stand on glass plates like frozen in a floating movement.

This is bling-bling, this is decorative, but no matter what colour the pearls are, you will discover your reflection in them - vanity becomes visible. Regard yourself in a precious object, let your image be absorbed by a work of art, become a part of it and make it a part of yourself in the act of contemplation. Most visitors cannot resist to taking a photograph.

In a second type of work glass blocks form fragments of fake brick walls. The spotlights' reflections create illusions of rainbow coloured flames above them, lending them the appearance of blazing fireplaces. Othoniel explains these works to be inspired by the "Greenwich stonewall riots" in 1969. And here we are. Would it be offensive to say his works perfectly fit into the cliché loft with pink curtains, (lots of) coffee table books and a wardrobe full of designer fashion? It is something about their colours, their style - or stylishness. Yet they are not only 'fabulous' looking, beyond the shining surface hide those meaningful details like the flames alluding to oppressed but inextinguishable powers, set free in a protest that became the birth of a movement.

A visit to Delacroix Museum helps better understand both artists' inspirations. Located in the artist's last home it is remarkably small and descent. Although quite famous by lifetime, Eugène Delacroix did not live in luxury (especially when compared to the splendour of Gustave Moreau's last residence that equally serves as museum today). The cosy atmosphere of blood-rusty-red walls, traditional hanging of numerous paintings closest above and beside each other plus the effects of genuine historic furniture mark a stunning difference to flashy white cubes (that by the way are so 20th century... but few dealers have understood it yet). Only the overwhelming flower perfume (I will never understand how anyone can use "breath-taking" as a positive term), that blocks your way in thick clouds is not necessary at all.

Amongst Delacroix' watercolours and oil paintings the contemporary works seem surprisingly well integrated. For his 2008 work series/book project L'Herbier Merveilleux (The Wonderful/Magical Herbarium) Jean-Michel Othoniel travelled the world to take photos of flowers and write a text with anecdotes and attributed meanings for each. Two pearl sculptures and some preparatory sketches demonstrate how much the natural beauties have influenced his work in general. In this context you suddenly recognize the soft movement of leaves, the airy shape of flowers, in Othoniel's sculptures.

In some aspects Johan Creten's Wallflowers resemble the abstract vivisecting works described above, the multiplication of a pure biological form leads to a new aesthetic. Scente di Femina (Scent of a Woman, like that classic Al Pacino movie) is different: A female torso covered with rose blossoms, perfume turned visible, not to mention the obvious eroticism. Human figure and flowers engage in a symbiosis that can be interpreted in different ways. We are a part of nature, but we absorb external entities; a perfume becomes an essential part of a human personality like the clothes we wear. As human beings we create ourselves in assimilating the wool of an animal and the scent of a flower.

In this great little exhibition the museum not only succeeds in presenting different artistic techniques in harmonious unity but also in explaining some ideas behind these works. This is what good curating means.

P.S.:

If you have read attentively you might wonder, what is the third exhibition at Perrotin? The answer is abstract painter Pieter Vermeersch, and this is surely worth a visit, too.

Perrotin Gallery, 12 January-23 February 2013

Delacroix Museum, 12 December-18 March 2013

Comments