Installing... Installing... Installation complete. Moving Is In Every Direction at Hamburger Bahnhof

- Christian Hain

- Mar 24, 2017

- 8 min read

Updated: Mar 25, 2020

(Berlin.) “Art installed in space” may appear under many names. “Narrative spaces” would be one, “environment” another. The curators of Moving Is In Every Direction – title courtesy of Gertrude Stein in reference to “non-linear narration” – at Hamburger Bahnhof Museum like the linguistic infighting of the past which saw “installation” emerge victorious at some point in the 1980s. It’s fun to poke around terms and definitions, Bahnhof’s press conference was particularly concerned with this. They quoted the “sociology of architecture” and the need for “open spaces” in city planning (undesignated areas, you go to meet friends, do a street performance, or buy drugs). Apparently, these are sometimes called “narrative spaces” too, which sounds not quite right: A space offers a stage, an inspiration at the most, a potential, but every narrative needs to be told, needs movement in whatever direction. Narration happens. The museum VIPs further focused on the German verb “begehen” in its meaning “to walk on/over/upon“ (also: “to inspect a site”), but overlooked the word's second meaning: To celebrate a special occasion.

According to Allen Kaprow who preferred the term “environments” for his pioneering works of the 1950s (there have been precursors), a basic definition would be “a work of art that concerns the whole space”. This initially referred to a situational practice, a form of happening; only later the genre got museum-ized, i.e. made preservable in collections and time. Reason enough for Bahnhof not to clone a finished work of Kaprow’s, and show a catalogue and photographs instead.

I’m a simple guy; you know this if you read this blog regularly. To me, it’s easy: If it’s neither a painting, nor sculpture (and no assemblage, drawing, or ready-made, either), it’s an installation. Or, better still: A combination of more than one, discernible, parts, treated as a single piece (by the artist), and intended to be shown – and sold! – as such. Two or more sculptures presented under one title: An installation. A painting and a sculpture meant to be inseparable: An installation. Found objects beneath a group of paintings: An installation, indeed. A video projected onto a painting, with a loudspeaker broadcasting voices, and a performer performing in the background: You guess it. The individual bits become parts of the bigger p̶i̶c̶t̶u̶r̶e̶ installation, to form a single entity. One might argue, whether this turns some casts of Rodin’s Bourgeois de Calais (those not sharing the same support) into an installation, and others not. Also, performances may happen on an artist-defined stage. Shall we just continue to the show - after all, what’s in a name?

Most works are sourced from Bahnhof Museum’s proper collection, with additions from other Berlin based institutions. Before arriving at the first installation, most visitors will have a look at a participative performance - with sculptural elements... - in the main hall (a large open space itself). Adrian Piper made them install three “winged” walls, creating a sacral atmosphere, and a reception desk in front of each. On each wall, a different statement: “I will always be too expensive to buy.” “I will always mean what I say.” “I will always do what I say I’m going to do.” An artwork talking? An artist manifesto? Categorical, imperative even? “It’s not just a motto, it’s a pledge”?

Patrons are supposed to approach the interns behind the desks, and subscribe to a statement. Leave your data, sign a form, check in to the club. Or stay without, feel challenged to resist, if only from spite - don’t follow the rules. Don’t be calculable, don’t be a computer. Ok, well, just go on, subscribe, but don’t give a sh*. Everyone’s taking words too seriously.

This is The Probable Trust Registry. The words are written one below the other, the “P” under the “T”, the “R” under the “T”, but “Trust” broke the line, and only the second “T” finds its place under that “P” (come on, it’s not that hard to understand, just write it down). In the end, it doesn’t matter but visually. And finally, the “rules of the game” are on display. This is confusing. No doubt, everybody involved can, and should, be trusted, and still: They say, “the receptionist” will not disclose the address/contact data “to anyone”, yet the same data will become confidential property of “[the Museum]”. Nowhere in this, Adrian Piper appears, yet in the end, an Adrian Piper Research Archive Foundation Berlin (APRAFB?) agrees to all conditions. I’m not paranoid, but this disclaimer might not have been checked by their legal department.

Signatures will be preserved separately from all confidential data, and after the exhibition’s close, the participants will be sent a list. As mentioned above, this is not a part of Moving Is In Every Direction.

The show spreads over Bahnhof’s West Wing and a second exhibition space. If Adrian Piper lured you into the main hall, you will probably not return to the entrance and the show’s starting point, but proceed to the Wing immediately. It’s also the better part, by far.

The exhibition design continues a trend, we’ve noticed lately, at Stoschek’s for instance: One room per work only. Makes the curator’s task easier, no need to care about transitions and homogeneity. It also lessens the effect of an exhibition appearing as a meta-installation. As usual, here are some remarkable works in (more) detail:

Wolf Vostell’s Electronic dé-coll/age Happening Room (1968-82) once allowed visitors to walk on broken glass; today it’s closed, a conventional artwork to contemplate from the outside. Still an installation. The Fluxus artist made a sandbox of shards with TVs and moving elements, e.g. a deadly sickle. Media assaulting the mind, the world, shattering - what? The contemporary context was Vietnam.

Is this Ceal Floyers? No, just flowers, and birds, bugs, and bees, but no seals (see? I told you, I’m a simple-minded guy). An assembly of ferns, a conference to which every participant brought his own oxygen supply – that could be a business idea in China -, or a meeting of Vegetarian Binge Eaters Anonymous? With his green waiting room, Marcel Brodthaers sought to express something about winter gardens being the tamed version of exotics (today, you’d call it “inclusion”). On the walls around, historic posters of natural history. A TV with a camera on top selfies you in the green, go play at Nam June Paik’s Buddha, maybe. It’s fascinating, it really is!

Susan Philipsz’ War Damaged Musical Instruments (Shellac), 2015, with six speakers suspended from the ceiling could be a left over of that recent musical show. The recordings of a melody played on war-damaged instruments is charged with a narrative that needs to be told separately.

Ceal Floyers, now really, also unearths a narrative, quite literally as we listen to the sound of shovels shovelling in Dolby Surround. Something is happening, or has happened, and the connotations are not happy. Digging a – their own? - grave, you dig?

Strangely, all acoustic artworks are called “sound installations” even if there’s nothing else to them. And a similar thing happens with films. - Whoever came up with the idea to call art films “film installations”? Following this logic, you might call every painting a “painting installation”, every sculpture a “sculpture/solid/stone/marble installation”.

I hereby formally refuse to call Stan Douglas an installation artist (anywhere to sign this? Ms Piper, please?). These are “only” photos, great as always, but unrelated other than belonging to the same series. He’d sell (already sold) them one by one.

A film in a separate room does not belong to this “not-ensemble”. Opposite the screen an open door and a barricade, is this part of the art, or not? Turns out not, a technicians tells me and other random visitors: “There’s just stuff behind”.

What if you place a stonen bench with stonen books in front of the screen, as did Sharyar Nashat - Will it make it an installation? Maybe. At least you no longer can justifiably call it a film and include its totality. In this particular case, the sculptural additions deter from the film featuring a studio, or factory, with more stones. Wait - This is actually an installation of the curators playing at artist! It's two distinct works: Cast in the Same Vein, 2011, the sculpture, and Plaque (Slab), 2007, the film. Got me there.

Fischli/Weiss’s Untitled (Questions),1981-2003, seems the “Anti-Piper”, posing multilingual questions with a battery of noisy projectors (the sound of thinking?). “Do I have to be cheerful?” “Could we complain about most things?” “Does violet go with yellow?” A berth on the floor could symbolize the potential manifestation of ideas.

Art sucks, no: art and socks. From Thomas Schütte. His Moor’s Life trilogy, shown in three rooms next to each other, portrays a fictional artist and his household. True installations, ensembles of sculptures and objects (ready-mades, so to say), it’s a sort of three-dimensional painting. Another work by the same artist appears as a mental laundry with words on blankets that hang from washing lines.

But Moving...’s highlight is Ilya Kabakov’s Torn Down Landscape. At the far end a painting, to the sides numerous papers with thoughts extracted from the patrons’ minds. Sadly, it’s only in Russian with German subtitles. Really sad for a museum that wants to be of international relevance, in a city that wants to be of international relevance. Tiny cartoon animals accompany the words where the rest of the paper is left blank. If there’s a relation between animal and thought, Kabakov has hid it well.

Who knows what these thinkers really see before their mental eye, the indescribable in words? “If you stare at that blackboard for long enough, something will happen to you, of course, but why should I stare at that blackboard?” “The things I’ve been told about it were way more interesting than this work itself.” “Will somebody buy this nonsense?” A humorous, a great, work of art.

With some installations, you wonder if all impressions are intended, and part of the experience. Descending the stairs to Bunny Rogers, you’ll notice two things first: Paper snow falling in the doorway, and a chemical smell that reminds of iced tea. The floor is covered with that fake snow - or is it supposed to be ashes? -, there’s a piano, fake (i.e. electric) candles, and a screen showing an animated film. It’s all artificial. Bunny Rogers claims, her topic were the Columbine high school massacre. Whatever. We just have to believe her. Although it’s all fake, and those shootings were true news. The smell remains the most intriguing part.

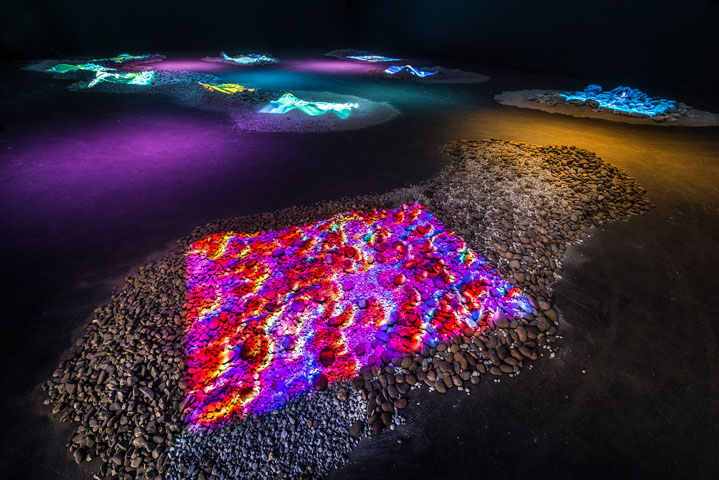

Pipilotta Rist pushed the lava lamp to the extreme with simple and colourful images projected to “beaches” - sand and pebbles that create an underwater effect. Looks great, really decorative. Not in a bad way. Coloured sand in a glass also looks similar.

The Riecks-Halls part is less good. But it’s here, where they hid their Kaprow, or the information on a Kaprow rather - catalogues under glass, a photo, and that’s all. Would you call it an installation in its own right? Don’t get confused and take the back room for another work by the same artist. This – monk’s or prisoner’s - cell, as far removed as it gets from German Gemutlichkeit, furnished with a mattress only, has been installed by Grego Schneider. Another nice work here, by Barbara Bloom, involves much text, the history of Nietzsche’s Nazi sister and miniature books.

One artwork you’ll spend some time searching for. It’s hidden in the East Wing, in the furthermost room over there: Beuys' The Capital on artistic currency in a new economy. Next to it, you’ll find a film on the artist, not as good as the one coming to a handful of cinemas all over the world, soon (it was at Berlinale).

The movements in every direction explore different limits of installation art. Hamburger Bahnhof succeeds in questioning the discipline’s boundaries – naturally overstepping them from time to time, and showing works that definitely don’t match the category. It’s a great experience, with surprising and fascinating works. In all honesty, this might be the best show at Hamburger Bahnhof for a while.

Several permanent installations officially participate in Moving Is In Every Direction, and they have not even been moved (several Beuyses, a Bruce Naumann, Robert Kusmirowski‘s fake subway station). On arrival as on leaving, I once more forgot to watch out for the Dan Flavin somewhere in the entrance area; it’s a neon I presume.

Moving Is In Every Direction, 17 March-17 September 2017, Hamburger Bahnhof Museum

World of Arts Magazine - Contemporary Art Criticism

Comments