Felix Vallotton, A Man of Many Styles

- (first published on artlifemagazine.com)

- Oct 24, 2013

- 4 min read

Updated: Mar 24, 2020

(Paris.) Grand Palais' second autumn exhibition presents Felix Vallotton, who is best known for his participation in the Nabi group from 1888 onwards. Where - according to the group's inner nomenclature - Pierre Bonnard was "The very Japonized Nabi", Paul Sérusier "The Nabi with the Glowing Beard", Maurice Denis "The Nabi with the Pretty Icons" and Paul-Elie Ranson "The Nabi even more Japonized than the very Japonized Nabi", Swiss born Felix Vallotton was known as "The Foreign Nabi". Apart from their preoccupation with esotericism and Japanese art, this group of painters obviously shared a sense of humor. Without wanting to over-interpret: the relaxed self-irony apparent in their choice of nicknames tells much about the change in attitude taking place in the second half of the 19th Century, when dead-serious Academism was buried. The road to Dadaism opened long before the 1910s.

Felix Vallotton is special. He had not a distinct style of his own; he had many. Vallotton was influenced by Art Deco, by Symbolism, by Japanese prints and much more, and he could adapt his work to them at will. Different styles may even coexist in the same painting.

Vallotton's experimentations with photography are particularly fascinating. He often used photographs found in magazines or taken by himself with his Kodak No 2 camera, which - also shown at Grand Palais - now belongs to a private collection (of paintings? of photography? of artist memorabilia?). Photography has been of major influence for the development of modern painting; without a chance to equal the new technic in realism, painting had to seek new ways to reassure its value. Where "artistic" meant true to nature before, it now had to be redefined. This struggle that had begun in mid-19th century is still evident in Vallotton's works of fifty years later. Sometimes, he painted photo-realistically, and then again he exaggerated details - forms, colors - to make an image less "real", and thus more meaningful - more artistic (accuracy can mean more than realistic depiction). Willingly naïve/cartoon-like (Bathing in Étretat, 1899), Impressionism à la Dégas (On the Beach, 1899) or realistic portrait (Decorative Portrait of Émile Zola, 1901), what are the means of painting to express the same or even more than a photograph of the same motif? The transfer from photo to canvas can transform a motif in many different ways.

Vallotton's (self)portraits are mostly realist, and always lifelike (Self Portrait at the Age of Twenty, 1885; Gertrude Stein, 1907; Félix Jasinsky Holding his Hat, 1887).

His landscapes are about color and atmosphere, rarely about nature (e.g. Sunset. Grey-Blue High Sea, 1911).

For today's viewer it might be amusing to look for inspirations, Vallotton gave to other artist: A face in the foreground of the Symbolist La Valse (The Waltz, 1893) reminds of Klimt's Kiss from 1903, and the sufferer's backhead in La Malade (The Ill Woman, 1892) is hyperrealist just like Gerhard Richter's famous Betty, painted almost a century later (1988).

And then, there are nudes. Lots of them. The sheer mass of these works more than hints to their commercial success, and somehow damages that old "antique tradition" excuse. Before the Internet, there was Playboy Magazine, and before Playboy Magazine, there were painters like Felix Vallotton. Nudes in every variation, to no special aim other than to please the eye, and maybe to provoke conservative furor. Non-explicit pornography is a great oxymoron, yet the definition comes to mind in front of these women playing with each other - a game of Checkers ("Dames" in French), strategically placed between the spread legs of one of them (Femmes nues jouant aux dames/Naked Women Playing Checkers, 1897). There are also nudes playing with cats (yes, etymologists are sure, that term has already been used in the 19th Century).

When a dachshund is petted in a Turkish (Harem's) Bath, we may ask if it's a wishful self-portrait. Another highlight (or "bottomlight") is the Étude de Fesses (Buttocks Study; probably not inspired by Courbet), which could be useful in Medicine Class to illustrate the symptoms of advanced cellulitis.

Strictly decorative and focusing on ordinary, unexplained, persons (as opposed to the classic tradition), these paintings don't need a story, mostly not even a situation. The few exceptions include Vallotton's version of Manet's Olympia: La Blanche et la Noire (The White and the Black Woman, 1913). Here the black servant is curious, knowing, watching pensively while smoking a cigarette; she appears much more emancipated than in the original, which today is commonly praised as "the first modern painting in art history".

Only when the nudes get down to action, Vallotton is bound by tradition: It must be important for the story, and the story is mythology. But Vallotton were not Vallotton, would he not surpass tradition. He captures the Pantheon's never-ending orgy of girls, gods and satyrs from a mocking distance, and could thus go further than others dared. Irony is all that saves a girl's grabbing a dotard's genitals from obscenity (Nude Woman Teasing a Silenus, 1907).

The scenes of elopement by gods in disguise approach the ridicule, which has probably ever been inherent to the myth. The battle of the sexes sometimes seems very modern, with emancipated scenes of female violence (Orphée dépecé/Orpheus Cut to Pieces, 1914).

Dungeons and dragons continue with Persée tuant le dragon (Perseus Killing the Dragon, 1910), a joke on St George and every other dragon story. Andromède debout et Persée (Standing Andromeda and Perseus, 1918) with a red woman, a green dragon-bull-snake and a blue knight tearing the black sky apart is much influenced by Expressionism, another contemporary movement, Vallotton was not afraid to adopt.

Again, in these works, we find ever-different styles, to question reality and realism. In the end it does not matter how something is paint, as long as it is paint. Vallotton seems to defy any difference in value between different styles. And not to forget: there are no (authentic) photographs of mythological events.

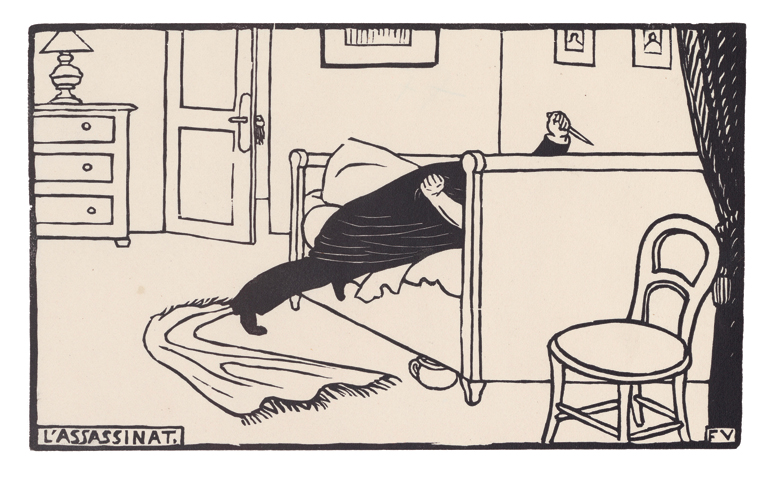

What else? Woodcuts, for example. Just another discipline, Felix Vallotton mastered. The abstract banality of crime stories ("faits divers") seems best reflected in this impersonal, often caricaturesque technic: L'assassinat (The Murder, 1893).

With the woodcut series C'est la guerre (That's War, 1915/16; the expression is quite common in French, to describe an unpleasant situation, e.g. when the deadline for an article closes in), Vallotton depicted his WWI experiences. Here, realism is horror.

Felix Vallotton, Grand Palais, Paris, 02 October 2013-20 January 2014

Comments