Black and White, and Ambivalence. Kemang Wa Lehulere at Deutsche Bank Kunsthalle

- Christian Hain

- Apr 3, 2017

- 5 min read

Updated: Mar 25, 2020

(Berlin.) The Deutsche Bank Kunsthalle is always worth a visit, and especially so if you’re invited to one of their press previews. Although this time, something seemed not quite right. “Yeah, those figures were bad, really bad... Guess, they have to start economizing, somewhere...”, the disappointed faces around me seemed to say. The tour through the show felt much longer than usual, and even the artist arrived late (or not, in African terms), while hiding his eyes behind sunglasses - Berlin nights can get long. It was only in the very end, almost upon leaving, when we realized, we were wrong, and they finally served the much anticipated coffee and sandwiches. The outstanding quality of their catering is certainly a reason to prefer the embodiment of evil, world dominating, ultra-capitalism to every honourable museum. But maybe you are more interested in reading about art?

Fine then, here we go: A new year, a new Deutsche Bank Artist of the Year, for the eighth time already. Continuing the tour around the global markets, DB Kunsthalle’s next stop is South Africa, and there’s more to South African art than William Kentridge alone. Kemang Wa Lehulere, for instance.

Wa Lehulere’s work is all concerned with (black) identity, and his native country’s painful history. A series of works juxtaposes his paintings with those of Gladys Mgudlandlu who in 1964 became the first black artist to be granted a solo show in a South African commercial gallery. Her success under the apartheid state was not met with applause among the black population. After Mgudlandlu’s death in 1979, she was mostly forgotten until Keman Wa Lehulere, with the help of his aunt who as a child knew the artist personally, searched and found her former home. In this Berlin exhibition, we also see the photo of a mural his assistants have recently uncovered in that home.

The painting comparisons highlight the fundamental political change, and at the same time hint at potential continuities. On the one hand, Wa Lehulere’s life in no way is comparable to his compatriot’s suffering under racist rule. But what about the galleries, the collectors, in how far have they changed?

To be honest, there are good reasons why Gladys Mgudlandlu was forgotten, the tastes of Boer art collectors tended not to the avant-garde side. Her decorative images appear much less inspired than Wa Lehulere’s art today. Yet, he too has been shaped by “white” tastes and fashion. And he insisted on titling this series Birds of a Feather. The connection that makes them “flock together”, as the saying continues, is only the phenotype, or the race if you want. That’s exactly the attitude, Wa Lehulere is fighting against. He is self-reflective enough to realize the paradox of being interested in Mgudlandlu, of working on this subject matter, only for reasons of colour - with the underlying aim of saying, it doesn’t matter. In order to claim, colour doesn’t matter, you need to focus on colour matters. By associating himself with Gladys, he follows racist logics (“a black artist needs to be concerned with black history and black politics because he is black”), and he knows it. Many works can be interpreted in several ways, they emphasize different shades of the same story.

More works of Mgudlandlu’s are joined by chalk drawings of Wa Lehulere’s aunt who tried to remember scenes and views from the artist’s home. One of the “historic” works depicts dodos, a different native population whose encounter with European migrants did not turn out well.

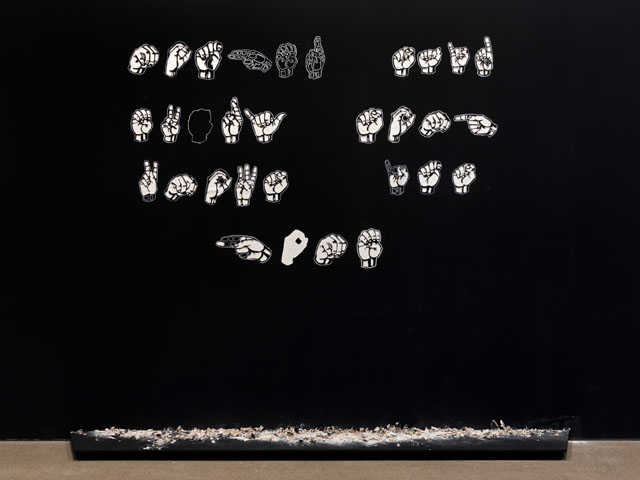

A film on Gladys Mgudlandlu includes the phrase, “I have words to tell you” in sign language, projected on black backs. A stamp, a label, that needs to be told in order to be removed. Another mural, a new one, and not only in photography form, features more signs of (American) sign language in white on a black background. - Was there not a story about a black South African “interpreter” at Nelson Mandela’s funeral who did not know a (meaningful) word in sign language? Right you are, Thamsanqa Jantije turned the Memorial into a memorable event for the wrong reasons; he became an internet legend, a global star for a quarter of an hour. In a way, he is an artist. There is no explicit evidence, that episode influenced Wa Lehulere, but who would doubt he knows all about it?

Below that black wall, the floor is covered with plaster dust. Still I wonder, how they did it, should it be a huge black stencil in the end? No, that’s indeed the back wall, all painted over, and the signs chiselled into it. The artist leaves a trace at the Kunsthalle.

The story told in significant silence reads in translation, “Mother said, every song knows its home.” Mama Africa has been deeply scarred by white frontier lines. Yet, it would probably be too obvious, naive, and as far removed from scientific art criticism as it gets, to comment: “black continent cut into, deformed and disfigured by the second non-colour”.

Deutsche Bank Kunsthalle further shows installations of deformed school furniture, taxidermied birds, and deserted bird houses. There’s even bird poo, white spots inside those houses, and occasionally dogs made of ceramics (-or china, like in “Chinese neo-colonization of Africa”?) outside. The background again is serious: When people were forced to leave one township, and got moved to another, their dogs were murdered. Living in a cage. The ceramic dogs are white Shepherds (if not huskies?), also the oppressors’ breed of choice. On a side note, I would not be surprized, if Wa Lehulere knew that film White Dog.

Another, much larger, installation has bibles and sets of teeth fixed in vices, ready to fly away, or brutally pressured. Belief, books and speech to fly away; belief, books and speech to trap the bird, tools used in different ways, like, in a way, dogs.

Kemang Wa Lehulere continues to raise question about “blackness”. You might be surprized by his own appearance, his name sounds far blacker than he is. The artist is of mixed origins with a white, Irish missionary, father - you know Italians and Spaniards of a darker complexion. Under the Boer regime, there was a test we learn, to formally establish negritude. The “pencil test” demanded to stick one into a person’s hair, and if it would hold, you were officially black. Which means, I am. Or maybe I have not washed my hair for several days. The absurdity makes about as much sense as medieval European witch tests. Wa Lehulere’s comment consists of musical notes on a canvas, written with his own Rasta locks (he now sports a more gallery compatible short cut).

In the end, speech, religion, skin colours, even pets are open systems, and can be used for different goals. The parrot sitting on one of the distorted school banks will repeat what he was once taught (or would, were he alive), and apartheid school were not overly concerned with a comprehensive humanist education (still, this seems a rather pessimistic view on the human mind’s ability to innovate, and learn by itself, even opposed to imposed doctrines).

Kemang Wa Lehulere, Bird Song, 24 March-18 June 2017, Deutsche Bank Kunsthalle

World of Arts Magazine - Contemporary Art Criticism

Comments