Abide the Lawrence Abu Hamdan, at Hamburger Bahnhof Museum

- Christian Hain

- Nov 5, 2019

- 5 min read

Updated: Apr 1, 2020

(Berlin.) Apart from Cevdet Eret’s musical trip to Bergama, and not officially part of the series Works of Music by Visual Artists, Berlin’s Hamburger Bahnhof is showing a second exhibition to engage the patron’s sense of hearing these days.

We’ve met with the work of Lawrence Abu Hamdan before, on the occasion of Berlin ART Week 2018 at DAADgalerie, a German foreign exchange student programme with a branch in contemporary arts. Back then, it was a group show and his contribution all about walls and sound, it was memorable. Today’s solo is rather small, and the best part stands at the beginning: A series of works under the title Disputed Utterance, that - not without a pinch of dark humour - inquires into the misgivings of spoken language. The artist has collected examples of misunderstandings that became the all-decisive factor in criminal cases, for example, we – well, not quite: hear, but: learn of a doctor in the US who stood accused of telling a drug user, he might as well “inject those pills” (after grinding them, supposedly). He was acquitted because of his strong Greek accent that caused him to never pronounce the “t” in “can’t”, and his claim to have stated: “You can’t inject those.” Doubts remained. Or the tragic case of a Dutch tourist and her fatal accident at a bungee jump in Spain, when she misinterpreted the exclamation “No jump!” for “Now jump!”. The bungee instructor “only pleaded guilty to a poor command of English”, yet was convicted of manslaughter nevertheless. Or, thirdly, an emergency call in London that left the operator with the understanding of a single word: “Murder” (presumably not “of crows”). On arrival at the caller’s home, police found an elderly woman who, as it eventually turned out, had died from natural causes - but did she not imply wrongdoings in her last moments? The case was closed when linguistic experts concluded, the French born “victim” bowed out with a four letter word in her mother tongue – or in French, it’s actually five: “m-e-r-d-e”. As a Scottish person might comment: “Naebody modderd ‘ir!” Lawrence Abu Hamdan adds a different example of Caledonian dialect, evolving around a presumed Glaswegian gangster and the question whether “thrrrnie windae” translates to ”through Ernie’s window”, or “through Ronnie’s window”... Ultimately, Ernie was proven guilty.

Even politics step in: President Trump correcting – or: changing – “would” to “wouldn’t” in a quote about Russian interference in the elections. “I have [seen? the word is missing in Abu Hamdan’s work, and it seems an involuntarily omission – or is it?; could be “met” or “spoken to” as well] President Putin, he just said, it’s not Russia, I don’t see any reason, why it would/n’t be.” For this one at least, we can be sure of its authenticity, for the rest, we need to trust the artist’s word, something you’d better avoid in general – but of course, it wouldn’t matter much, had Abu Hamdan imagined some events instead of spending hours perusing legal case studies.

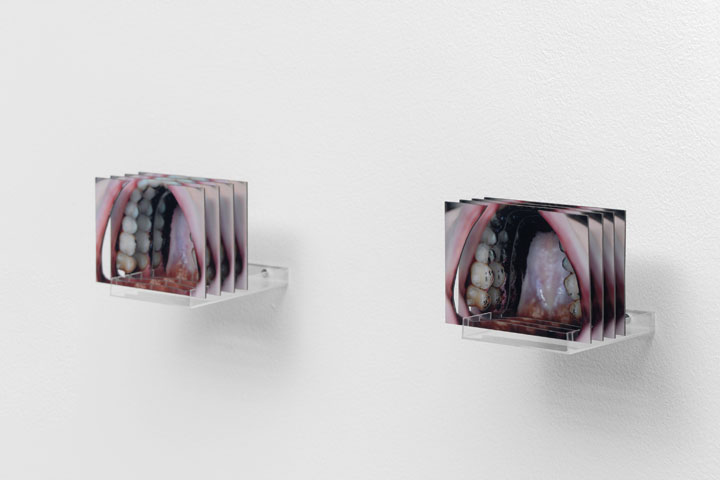

All of the above, and more, examples are presented in the form of short(est) stories on plexiglass, hung next to “palatographies” – photographs, or more accurately: photograms, of oral cavities. To create these, the speaker takes a mouthful of charcoal and olive oil with a blank paper, then pronounces a sound important to the particular case. The technique is otherwise used to document and archive endangered languages.

The exhibition continues in a short corridor with flickering monitors on both sides: Mobile phone filmed scenes from a desert wasteland, and people shouting in Arabic. The wall text tells us, these are the Golan Heights and it’s 2011, when families (and fighters, potentially) who for decades communicated across the border, finally stormed said border, which led to several deaths in Israeli gunfire. Their voices are ambiguous, expressing the joy of meeting again and the terror of landmines simultaneously. There were none of the latter, which fact helps the installation to its title: This Whole Time, There Were No Landmines.

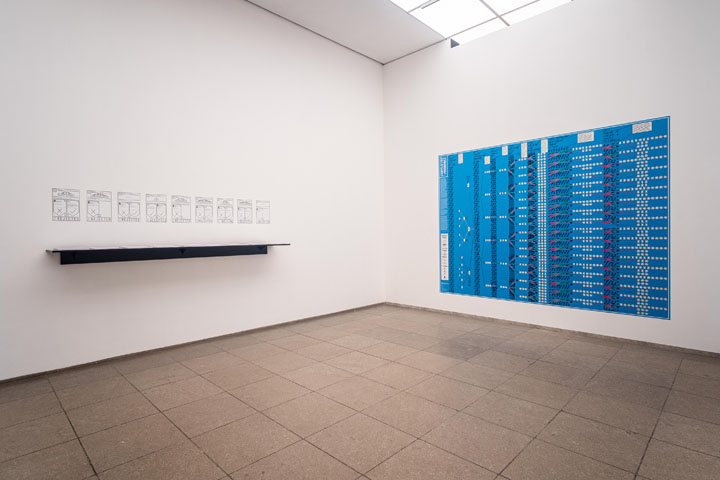

Finally, a separate room, and the stories of Somali immigrants to – well, someplace where the grass is greener (they believe). Seems, there are lots of different languages and dialects spoken in Somalia, just like in other, and even European, countries; this raises problems when EU immigration services resort to a computerized linguistic test to determine authenticity of origin. It not being cool – or legal - to take a DNA test, yet taking those people at their word not being advisable in every case either, a Swedish company invented that test using some sort of artificial “intelligence”. As a result, many self-identifying – and actual! – Somalis are rejected entry because of a computer “judging”, they would not speak like thoroughbred Somalis. (Those who are accepted of course will, and need to, loose their mother tongue and cultural otherness soon in glorious “equality”.) For further context, we learn about the history of Somali language*s, and are confronted with anonymised test results on takeaway posters – you may grant them asylum in your living room! All very informative, and yet... – it’s not overly artistic, don’t you think?

Returning to that first series, though: brilliant. Who was it again who said, “today’s fatherland is the mother tongue”, or something to that effect? Ah yes, thank you Google/DuckDuckGo: Emil Cioran, “One does not inhabit a country; one inhabits a language. That is our country, our fatherland — and no other.” (If you think you’ve heard this somewhere before, we might be playing the same video games).

Titles matter, and in the case of this show, it's The Voice Before the Law, to which the curator accords only two meanings. - Referring to priority: voice imports over law (the human above legality), or, literally, referring to a trial: the human voice as a defendant before judge and jury. There’s more to it. Never underestimate an artist’s education, and Before the Law, one of Kafka’s best-known stories is still being read around the world. Probably more important than an anecdotical literary allusion: We could infer temporal prevalence here: “In the beginning was the voice/word...” that gave the law. Once again, we don’t know much about an artist’s heritage, but most probably his cultural backgrounds link to one of the Abrahamic religions (yes, dear millenials, we know, there are also Hinduists, Shintoists, Scientologists or even Bokononists in Beirut, his place of residence, but there’s the voice of probability laws, too). Here we are at the Babylonian confusion.... which, by the way, was not the worst thing to ever happen: Despite potential casualties (see above), misunderstandings are important, even crucial, for a pluralist and diverse world (the definition of “I” and “we” is “not you”, and the will to differ, to do your own thing instead of understanding everybody else's lies at the very root of every culture). Mutual misunderstandings made and still make all the differences, they keep the world alive and interesting - To err is human, humans interpret and create; computers don’t. But back to art, and surprise: You could even turn that understanding around, and read: First, there must be a - human! - voice, and only then can there be a law, which would be a complete refutation of natural law. There might be still more to this title, go and think yourself, language is fun, it’s not binary but open to individually unequal interpretation (which, of course, might be just too complex for the Digital Age).

Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s The Voice Before the Law at Hamburger Bahnhof Museum is a nice little show to visit this autumn, and should you want to interest somebody in a visit, you could mumble about “vices ‘for the loo”, that should work. Or keep it more mysterious: “Low rents a boo ham Dan”. Whatever you do, don’t expect to walk away from a defamation case by claiming, “Your honour, I was merely likening the accuser to an idealist German philosopher, Immanuel ---!”

Lawrence Abu Hamdan, The Voice Before the Law, 26 October 2019-09 February 2020, Hamburger Bahnhof Museum

World of Arts Magazine – Contemporary Art Criticism

Comments