A Picture is Worth a Thousand Lies: Stan Douglas at the Fruitmarket Gallery

- (first published on artlifemagazine.com)

- Nov 23, 2014

- 5 min read

Updated: Mar 24, 2020

(Edinburgh.) Uir joorney tae th' UK teuk us faurder north than juist Lunnon, as we gaed oan tae Auld Reekie fur th' Fruitmarkit Gailerie (an’ th' watter o' life, an' a fitba match), ken? ... Eh, sorry (and thank you, online translation tools). Edinburgh is not only the capital, but the cultural centre of Scotland, and despite its being more set on performing arts and literature, contemporary art is not all out of focus. The Fruitmarket Gallery currently presents an exhibition of Canadian artist Stan Douglas who rose to fame in the 1990s with photographs and film installations that elevate anachronism to art.

In Stan Douglas’ world, it’s all 1940s again, and we feel part of a gangster movie or a crime scene photograph by Weegee. In a play on reality(/ies) and images, those men kneeling on the floor and playing dice from the Midcentury Studio series could well be Humphrey Bogart or a henchman of Bugsy Siegel’s. In truth, the whole scene has been staged by Stan Douglas in 2010. Up to the least detail nothing is “real”, the “authentic” dollar notes have been reprinted and even the traces supposedly left on the wall by previous games have been scratched in by the artist (~’s assistants). But what does it mean to declare an image “false”, in how far can depiction ever be deception?

In press/reportage photography it is strictly impossible to know what is “true” – defined as unaltered observation -, as opposed to “fake” – the unaltered re-enactment of an observation at best, an uncorroborated invention at worst - , not to speak of images that are introduced in a fictional context - a film, an illustration to a novel - in the first place. Every epoch, every era, has a style, its “image”, perpetuated by film and photography. This visual identity is in part a mental construction: Where fashion, architecture and technology are “truly” typical, we constantly have to remind us that monochromaticity is not. (The world was not really black and white. Yet it suffices to see a monochrome image to misidentify the setting as pre-1960s.) We even extend the “type” to human faces that "match" their era. Stan Douglas' portraits of the Malabar Faces series thus appear if not authentic, than to show time travellers from the past; these people perfectly represent our idea, our image, of the 1940s.

Just like words, pictures have denotational and connotational meaning, and all difficulties arise in separating information from interpretation. What is imminently visible can only be “true” in itself, given as such; it's our our judgements that are erroneous. Assumed context and story can be considered “false” like the date pretended in a picture’s title. But does deceit matter, if the result is accurate? Stan Douglas follows the same approach as almost every historical TV documentary today, where information is not told and taught, but played and shown - whence this obsession with “recreating” past times? The viewer becomes the simulacrum of a witness. Images freeze a moment in time, even if they are not created at this exact moment themselves. Duplication may destroy the aura, yet not necessarily the “truth”.

As art, a photograph does not need any context, it is always “true” for and to itself. In art, it never matters if an image shows “what” or “how” “it” “really” was (quite a lot of quotation marks here). Finally, when reading (a historic newspaper for instance), we illustrate the story in our mind, and how could these internal images be “true” or “false”? In a way, Stan Douglas creates mental images, reproductions of something that is to equal parts seen and imagined.

His best known work is Der Sandmann from 1995, which earned the artist an invitation to dOCUMENTA two years later. Inspired by Siegmund Freud’s interpretation in The Uncanny (1919) of ETA Hoffmann’s tale Der Sandmann (1817), the artwork is actually two films combined. Both show the same place filmed within an interval of two decades, the former garden having turned to a construction site in the meantime. Both are shown simultaneously with an almost imperceptible cut line between the images. The cut manifests the time that has passed, yet the artist’s Frankensteinian effort to “sew” the parts together revives those moments long gone. The separation of space and time remains impossible, revisiting is repetition of the same; past and present constantly interact without ever overlapping.

Fruitmarket Gallery also shows Video, a - yes indeed: - video film following a woman in her ordeal with unnamed authorities. Stan Douglas explicitly calls it an adaptation of Orson Welles‘ film version of Kafka’s Trial (all these “ofs” again, like the re-enactment of a photo of a moment past). There is no distinguishable soundtrack, only distant voices that might or might not be other gallery visitors in the next room (there were also tripping feet, birds resting on the roof or mice living in the walls; we’ve actually heard the same noises at night in our B&B). The heroine waits in a crowded staircase, is questioned in an office, visited and menaced by men we instantly identify as secret police. Again, it’s about all the interpretation of images that offer no text. The visual style hints to the 1960s (a guess, nothing more), in any case a time when the use of a cell phone alone did not suffice to file your personality and register your fingerprints. It could be important for interpretation that unlike the majority of Stan Douglas’ works, this film is coloured, and some years ago you would have used the same term to refer to the actress (and the artist himself, a fact he does not habitually emphasize in his art). It might hint to immigration and racism as underlying topics.

The most recent work at Fruitmarket Gallery is ca 1948, a film that can be downloaded as an app. Once installed, it offers a virtual visit to two historical sites in Vancouver: Hogan’s Alley, and The Second Vancouver Hotel. Some dialogue reinforces the film noir atmosphere. On the downside you need an iPhone or iPad to enjoy the artwork (might give an idea of who’s sponsoring the Canadian Film board who sponsored the artist), it won’t even run on a regular Mac. The “Interactive Film” genre enjoyed brief popularity after the invention of the laser disc (way before the DVD), and it’s not clear if this use in art can revive it. Thankfully both places “exist” also in photo form. In theory, they represent a recreated but realistic environment, yet the images in the app and the photograph in the exhibition look much too good to be true. Superficial clarity reveals the falseness, every trace of imperfection has been eliminated to create the typical dead perfect picture that is just as perfect as death. In all its hyperrealism, Hogan’s Alley is an artificial picture, presenting the world not as it is, was, or could ever be in a human eye. It is thus related to the Corrupt files series.

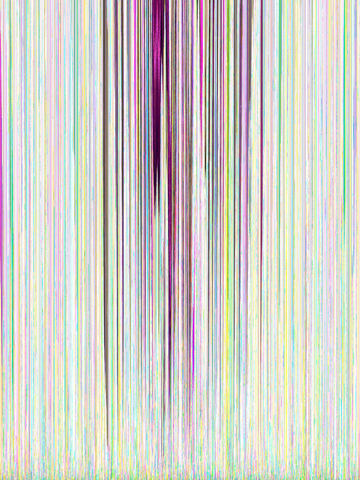

Here, Stan Douglas presents image data of photographs, a visualisation of computer files. These lines of colour don’t portray the world but depict information, strangely reminiscent of abstract painting (Gerhard Richter style). Albeit “true” copies of reality, the human eye won’t recognize them as such. They are written in a language that belongs to machines - even the geekiest photographer won’t be able to imagine an image on the base of these patterns -, and the files being damaged, they can never be translated. Is the information they hold “true” or “false”, “1” or “0”?

When an exhibition leaves you with more questions than answers, it is always a good sign. Stan Douglas’ art is both brain food and eye candy, nothing wrong, or “false”, with it. Aye, it was a nice visit to Scotland, the Fruitmarket Gallery, the whisky etc.

Stan Douglas, Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh, 07 November 2014-15 February 2015

Comments