So many questions: Bertrand Lavier, Centre Pompidou, Paris

- (first published on artlifemagazine.com)

- Oct 5, 2012

- 7 min read

Updated: Mar 25, 2020

Paris - Centre Pompidou starts the winter season with an exhibition of Bertrand Lavier: "Since 1969". Untypical for a retrospective, a good part of these works dates from recent years and gives proof of the French artist's unceasing activity.

The show opened on September 25th, which coincidentally is Mark Rothko's birthday - or is it a coincidence? One of the presented works is actually a film showing nothing but Rothko's painting "Four Darks in Red". And here we are right in the middle of Lavier's artistic research: What is art, its media and genres? What is a creation, a product, authorship?

Things were still easy with readymades in Duchampian definition: take an existing industrial product and present it in an artistic context (eventually add a fake signature) but this was only the beginning.

If you were to present a readymade on a socle, what kind of a socle could it be? The answer might be another readymade, so Bertrand Lavier put a fridge on a safe. But is this still a readymade? Or two? An assemblage? Are these still the original objects or does one and one equal - one?

Usually readymades don't have a history. Encrusted yellow stains in Duchamp's urinal would have destroyed its character; the classical definition of a readymade tacitly included its unspoilt condition. Unlike Lavier's crashed car, an Alfa Romeo, that he presents just as he found it in a scrapyard. Now it tells - or hints at - a story, which is the story of somebody absent, unknown even to the artist; its damages are not the result of any artistic action. Lavier put the reflection even further - what happens, if an industrial product is actively altered by the artist's hand without really changing its character; where does artistic creation begin? A piano covered with black acrylic paint does no longer look like a "real" piano, nor does a camera treated in the same way look like a "real" camera. At first sight you might mistake them for resin sculptures, to which we are so much accustomed in contemporary art, but neither form nor colour has de facto changed.

And continuing in this spirit: Do place-name signs that feature a stylised landscape become "paintings" simply by the fact that Lavier has overpainted them?

The important point is that these products have not been used as a surrogate for canvas but they dictate the very form of the painting, they determine the artistic liberty once this liberty has chosen them. In a classical understanding the additional layers of paint are less artistic than graffiti on a road sign but on the other hand Lavier still creates unique pieces.

There are more variants of the fascination for these issues. We find a Teddy Bear with a stick up his bottom, and the toy does not look as if it appreciated (can't wait to watch "Ted" when it finally comes to French cinemas). The cruel pillar alone changes the object's appearance.

Lavier seems to be particularly fond of fridges and they certainly have a long artistic tradition as numerous artists have painted on them (Bernard Buffet, Jean-Michel Basquiat, ...). This massive white cube in our kitchen is a challenge, a provocation not only for artists, but also for ordinary people who decorate it with postcards, stickers and silly magnets. Lavier for his part put a red lips formed couch designed by Salvador Dali on top of one to ask about the differences in their conception.

One of these works is special compared to the rest: a rock placed on top of another fridge. A natural readymade on an industrial one, sure. But when you realise that it has been created in 1989, you might start fantasizing about the cold war ended by the Berlin Wall's falling rocks. However, this is the only work in the exhibition to which it is possible to imagine a political background, and it might be unintended.

Beside its mass production, it is the designation as a useful product that distinguishes a readymade from "genuine" artistic creations (though there are grey areas: sculptures moulded in several thousand pieces, forgeries of a painting in contrast to machine printed posters etc.). Now "form follows function" is no longer true for all industrial design and today's marketing departments know that it is often more decisive for an item to look stylish than to be of any real purpose. Maybe it all falls back to the person of the artist, who creates (or gives the order to create).

The basic principle of Sartre's existentialism is that human beings are free because their existence precedes their essence (first I am born, then I am a waiter, a banker, an artist,...), whilst everywhere else essence precedes existence (a dog cannot choose to become a politician or a journalist - which is a pity, btw. - and no, guard dogs are not a good counter example). For an artwork it is habitually the artist who defines its essence prior to its existence, like a company (as a legal entity consisting of Marketing, R&D, etc.) does for an industrial product. But in our examples Bertrand Lavier just enforces the essence someone else has predefined which could serve as an argument for their classification.

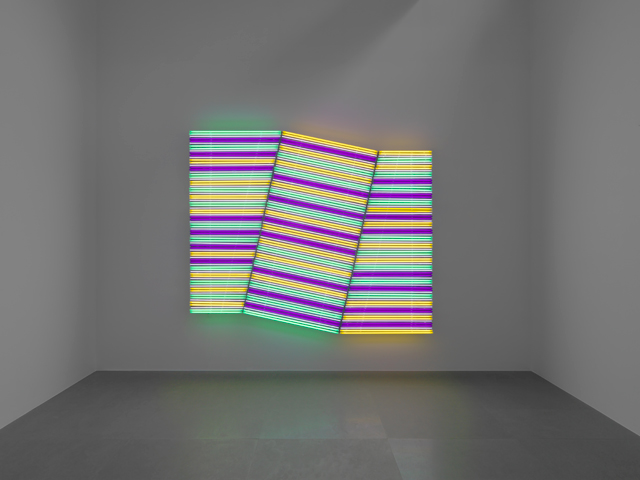

In art history it is common to find the same idea carried out by countless artists. The genre stays the same, the outer appearance changes: religious or historical scenes, still lifes, portraits of the same person executed by different painters... Now what happens if the outer appearance stays the same, and the technique changes? To inquire into this, Lavier took existing artworks to another medium. Frank Stella's abstractions reproduced in neon tubes and in a Gobelin tapestry are no longer the original works, the same is true for a mosaic of a pointilist painting by Signac, but are they Lavier's creations? And the Rothko film already mentioned above: the film of a painting simulates its existence or it reception, or neither of these? What if Mark Rothko had presented a film in first place? Would it be a piece of video art or a filmed painting, and Lavier's work, what is this - a documentary? What about authorship and originality in these cases?

Finally, how do people on the outside perceive contemporary art? A Walt Disney comic strip featuring Mickey Mouse on a visit to a museum might give an idea and Lavier brought the hitherto non-existent works to the real world. Again, these abstract paintings and Arp-ish sculptures are unique creations but also copies of something already existent in another medium/form.

Lavier furthermore investigates in the different genres of art, in the clarity of definition and separation (segregation?). You are convinced to know the differences between painting and sculpting, here you find two cubes of the same size: one of bronze, one of dried colour and both look the same.

A nice scenographic joke makes us observe other visitors through a window as they walk around a collection of works on a platform. A skateboard on a socle, a designer chair turned around that it does no longer look like chair but like a Tony Cragg sculpture, fake African sculptures, a kayak, ... These objects are the outcome of Lavier's occupation with primitive arts that began with an exhibition in Johannesburg in 1995. Maybe the concept of readymades was not Duchamp's invention at all, but is as old as are ethnographic museums?

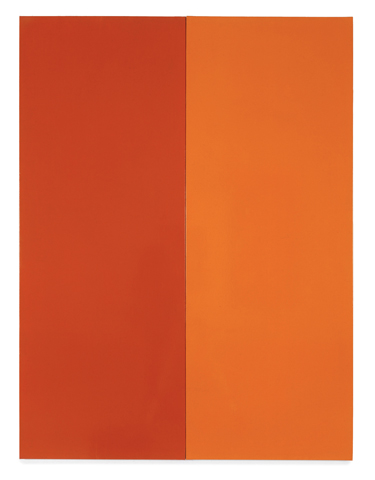

There is still another field of thought Lavier is interested in: semiotics, discrepancies between the signifier and the signified. A canvas half painted with the colour of one company, half with that of another - both carry the same name, but the result shows two distinctive colour fields.

A mobile by Alexander Calder on top of a fridge - ah no: it looks like a fridge, but this time it's a radiator - produced by a company called "Calder". And sometimes products are given famous names on purpose to benefit from established glory: in the 1990s a Citroën car model went by the name "Picasso"; Lavier presents a wing of it with the signature inscribed like a trophy, in a colour that reminds of IKB© (Yves Klein). As it hangs on the wall it appears shaped like a beast's head.

To prove how talking about an artwork can lead to misunderstandings, Lavier described a simple object, then ordered translations of the text in various languages and the object to be recreated according to these - the results shows variations, not copies, of the original.

To sum up, we have an artist who wants to know what art is, who continually examines its limits and defies existing definitions.

Often you have no clue what an artist is thinking of, and sometimes arises the suspicion he does not know it either. With Bertrand Lavier it is different.

The only critique may be the heretic's question: as fascinating as these reflections are - do I need to see art like this or is it sufficient to read about it? Apart from the problem with descriptions of art just mentioned above, we have to acknowledge that Lavier is also interested in form and colour - in a way his creations are aesthetic. Though still... The exhibition is not exactly a sensual pleasure. Head or heart, seldom art appeals to both. It is like in real life, perfection would be Stephen Hawking in Kate Moss's body, but well, your Latin investment banker likes Jason Statham movies and Icelandic ballerinas don't play Go.

We witness the work of intellect, examples of the art of thought. Maybe even the outcome is not that important, it is just a game, mental exercises for nerds. But is mathematics anything else? Or philosophy? We admire those guys who find (or create) unseen combinations, who create riddles for us to solve, but this is neither of practical nor of spiritual use, it leads to nothing and it does not need to. It tells something about thinking, about truth and causing and may thus lead to meta-knowledge. This is art.

Bertrand Lavier, “Since 1969”, Centre Pompidou, Paris, 25 September 2012 to 7 January 2013

Comments