Simon Hantaï's long March to Abstraction

- (first published on artlifemagazine.com)

- May 31, 2013

- 4 min read

Updated: Mar 25, 2020

(Paris.) Some days ago, on my way to the Centre Pompidou, I ran into a female friend who reacted with a somehow disconcerted smile when I told her how excited I felt to see "Hentai".

Only later, when using my cell phone to search the internet for a quick preparation to the show, I realised my mistake. The artist's name of course is Hantaï, and "hentai" a tout different thing.

I wonder how many people get this wrong when using Pompidou's hashtag #hantai.

Simon Hantaï was not even Japanese, but of Hungarian-German origin, born by the name of Simon Handl. When moving to Paris in 1948, he chose the Motörhead-style pseudonym Simon Hantaï, only original with the two dots on the "i", a French accent leading to the pronunciation foreigners would use anyway (there also is a Metro station called "Bienvenüe", but French people just say "Bienvenue").

Simon Hantaï made a successful career in French painting during the 1960s and '70s before retiring in 1982, from which year on he did not authorize any exhibition until his death in 2008.

Today, the Centre Pompidou shows an excellent retrospective, and we learn, Hantaï started with naïve (there it is again, but here spoken "ah-e"; so much for the French lessons for today) figuration reminding of outsider art (Jeune mouche s'envole / Young Mosquito Escapes or Peinture. Les Baigneuses / Painting. The Bathers). It followed an surrealist phase in-between figuration and abstraction, with organic forms floating through nightmarish landscapes. Blood cells, organs, thoraxes and bones; mapping the inner parts of a human body and mind. Hantaï frequently added genuine skulls of small animals (rats? or cats?) to his paintings. Femelle-Mirroir (Female-Mirror, 1953) shows what could be a beaver's skull on a naked body.

The artist seems much influenced by Renaissance's curiosity chambers, still-lifes and the Memento Mori motif; Mary Shelley would have been delighted too. After all the morbid play with exhumed body parts grants them eternal life in art. Even in France, this period is often forgotten, but the surrealist Simon Hantaï has not to hide before the confirmed masters of the genre.

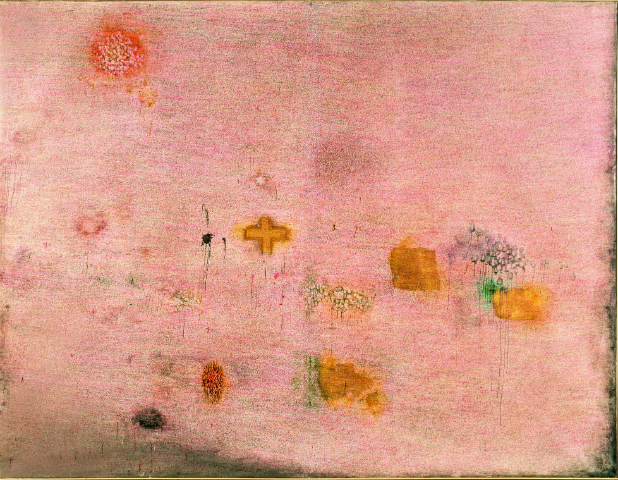

Leaving surrealism, Simon Hantaï continued on the path to abstraction. Signs and writings now take more and more the place of the earlier figurative forms. In Peinture (écriture rose) {Painting. (Pink Writing)} from 1958-59, Hantaï wrote microscopic text on the painted canvas, but it would take a Jean-François Champillon to decipher the messages (Wiki is your friend). Allegedly they are copies from religious and philosophical works; well: who wouldn't say that?

The use of signs is a sort of writing too, Souvenir de l'avenir (Memories from the Future) shows nothing but a white cross on a black background, pointing to death as the final frontier in an impressive work of art.

Occasionally there seems to be a relation to Graffiti, not in the sense of any conscious inspiration, but of a coincidental common style: Hommage à Jean-Pierre Brisset would make a magnificent whole car, and Simon Hantaï created it in a single day in 1955.

Not only in style Saint François-Xavier aux Indes (1958) appears as a parody of Jackson Pollock - usually Hantaï preferred neutral one word titles.

In other works, innumerably multiplied half-ovals that remind of torn out fingernails, or tombstones, or hills in a child's painting, fragment the canvas like a giant puzzle; the curators thought it a great idea to hang a work overflowing with these forms (Peinture, 1959) next to one showing what could be abstractified fingers, nail-less (Peinture. Touches Clairs, 1958-59). By now you should have realized: The Hantaï type of abstract painting invites to informal Rorschach tests. This is no hardcore abstraction; there are always forms that cry for comparison with known objects. The "nail" forms are also omnipresent in À Galla Placidia, a painting dedicated to the Roman Empress of the same name. It is meant as a complement to Painting. écriture rose, both having been created at the same time.

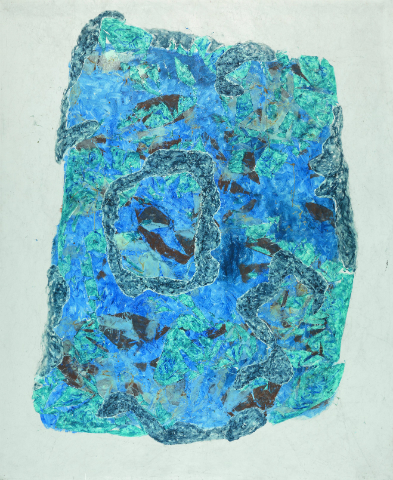

In the 1960s, Simon Hantaï developed a technique of folding the canvas with freshly applied color to create - or to "let be created" - patterns. Just to what degree he could influence the results remains unclear. More important, even these works still point to organic forms, a constant in his whole career from the early figurations over fantasist surrealism to abstraction. It is quite easy to see falling leaves in the Mariale series or human profiles in the Panse series, while the Meuns are reminiscent of Yves Klein's Anthropometries (those famous paintings that he created with the buttocks of willing female assistants for a brush.) Hantaï used inhuman technics alone to reach a similar effect.

Simon Hantaï created his least organic abstractions in the 1970s, with multicolored confetti storms and red or blue pool tiles, further perfecting the folding technique. Probably he needed all those years to arrive at this point, to let the body finally disappear.

When he had succeeded, he considered his artistic research - and career - finished. The works he created after his "retirement", and that have been found in his legacy, show variations of the reached conclusions, for the first time even in black and white. He came a long way.

Simon Hantaï, Centre Pompidou, 22 May-02 September 2013

Comments